Review of Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae, Volume II: Caesarea and the Middle Coast, 1121-2160

Review of Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae, Volume II: Caesarea and the Middle Coast, 1121-2160, edited by W. Ameling, H. M. Cotton, W. Eck, B. Isaac, A. Kushnir-Stein, H Misgav, J. Prince, and A Yardeni. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2011.

This epigraphic series (of volumes) will definitely be one the most important of the twenty-first century, certain to be used profitably and cited for decades to come. The entire corpus is slated to consist of nine volumes, organized according to major geographic divisions and major historical periods in ancient Judaea-Palestine. The chronological periods that constitute the focus of these volumes are the late fourth century BCE (i.e., beginning with the rise of Alexander the Great) to the early seventh century CE (i.e., to the rise of the Prophet Muhammad). The languages included in this series are Greek and Latin as well as Hebrew, Phoenician, the various Aramaic dialects (e.g., Jewish Aramaic, Samaritan, Nabataean, Northern Syriac and Southern Syriac), Thamudic, Safaitic, Armenian, and Georgian. It is also important to note in this connection that Early Arabic inscriptions are in the process of being collected and edited by Moshe Sharon for the Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae (and so they are not included in CIIP). The basic geographic parameters for the nine volumes are as follows: Jerusalem (and its surroundings); the Middle Coastline (including especially Caesarea and its surroundings), the Southern Coastline; the Northern Coastline (including especially the Galilee, along with Acco); the Golan Heights; Samaria; Judaea (without Jerusalem); Idumaea; the Negev; a final volume focusing on milestones from the entire territory. Parts of modern Syria and Jordan which were at different times part of the administrative unit which included Iudaea/Palaestina (i.e., Batanea, Aurantis and the Peraea) are not included in this series since they belong to territories covered by the Inscriptions Grecques et Latines de la Syrie or de la Jordanie, respectively. CIIP I. Part 1 (focusing on Jerusalem) was published in 2010 and contains inscriptions numbered 1-704. CIIP I. Part 2 (focusing on Jerusalem) was published in 2012 and contains inscriptions numbered 705-1120 (this volume, that is, CIIP I. Part 2, will be reviewed separately). That is, volume one consists of two parts, each published as a discreet volume, but classified as “volume one” (because all of the inscriptions hail from Jerusalem and its environs).

The volume herein reviewed is CIIP II, and contains inscriptions numbered 1121-2160. The lion’s share of the inscriptions in this volume come from Caesarea and its environs (inscriptions 1128-2107), while some of them (namely, inscriptions 1121-1127) )come from Apollonia-Arsuf (located on a sandstone ridge in the north-west section of the modern town of Herzliya, some seventeen kilometers north of Jaffa and thirty-four kilometers south of Caesarea), some of them (namely, inscriptions 2108-2114) come from Castra Samaritanorum (Khirbet Qastra, a site that is about three kilometers south-east of Sycamina and extends across several terraces on the lower slopes of Mount Carmel), some of them (namely, 2115-2145) come from Dor (near the modern site of Tantura, on a headland off the coast between Mount Carmel and Caesarea, more than eleven kilometers south of Tel Megadim and more than nine kilometers south of ‘Atlit), some of them (namely, inscriptions 2147-2160) come from Sycamina (= Shikmona = Tell es-Samaq, a settlement about one kilometer south of the promontory of Mount Carmel) and one inscription (inscription number 2146, called the “Seal of Georgius”) was found at Mikhmoret ( a site located on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea around eight kilometers north of Netanya and around eleven kilometers south of Caesarea).

For the site of Caesarea, there are subdivisions, something that is quite useful because so many inscriptions hail from this site. The major categories of inscriptions are: (A) Res Sacrae (Pagan Inscriptions, Synagogue Inscriptions, Christian inscriptions); (B) Imperial Documents, (C) Emperors; (D) Imperial Officials and the Two Praetoria (Governors and Senators, Praetorium of the Governor; Equestrian Officials; Praetorium of the Procurator and the Late Antique Governor); (E) Bathhouse; (F) Military People; (G); Decuriones and Inscriptions of the Colonia Caesariensis; (H) Varia; (I) Funerary Inscriptions; (K) Instrumentum Domesticum (Defixiones; Amulets and Rings, Weights, Lead Seals, Ostraca, Dipinti, and Graffiti); (L) Fragments, both Latin and Greek; (M) Vicinity of Caesarea (Binyamina, Crocodilopolis, Hadera; Kefar Shuni, Ramat , Hanadiv).

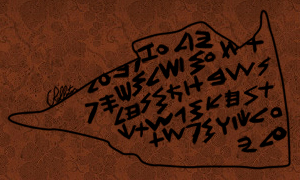

The standard entry for each inscription consists of the following sorts of data: a descriptive title and approximate date (e.g., “Corinthian capital with Greek monograms, 5- 6 century CE,” or “List of the twenty-four priests courses in Hebrew, 4-5 century CE”), reference to the find spot, a black and white photograph, readings (and for the Hebrew and Aramaic inscriptions a transliteration as well), a hand-drawing, a translation, a brief but detailed commentary, and rather copious reference to the most relevant secondary literature. It is important to note that within this volume, there are a fair number of inscriptions never before published. Also, some of the inscriptions that are included in this volume are now lost, but normally there were photos available of even these inscriptions and so these inscriptions are included in this volume, along with an accompanying photo (see p. vii). This fine volume also contains some really good discussions of things such as demographics (e.g., Jewish presence, Christian presence, Samaritan presence), discussions of roads, discussions of ancient territorial divisions. For sites that have been excavated, there is consistently a brief but very useful discussion of the history of excavation. Of particular importance is the fact that this volume contains an “Index of Personal Names” for Volume One (both parts) and Volume Two.

Readers will notice that the dates that are given for inscriptions are often fairly broad (e.g., “3rd-6th century CE”; or “4th-7th century CE”). This is, of course, a result of the fact that few inscriptions contain (or preserve) date formulae, many do not come from a primary archaeological context, and there are often not sufficient palaeographic benchmarks (diagnostics) within these inscriptions. I should note that most of these inscriptions were (re)collated during the process of the research for this volume (i.e., the person writing the article actually personally collated the inscription, rather than attempting to rely on existing photographs or hand-copies) and the date of the collation (called “autopsy” in this volume) is given within the entry for each inscription that was collated. Methodologically, this is such an important step forward.

Ultimately, I consider this volume to be absolutely superb (there are some minor problems with stylistic consistency, but with a volume of this size, with so many contributors, this is entirely understandable). I recommend the volume very highly and without reservation. Indeed, from my perspective, I would suggest that no scholar can afford to ignore this volume. It is a peerless addition to the resources available for the ancient epigraphic realia.

Christopher Rollston, Visiting Professor of Northwest Semitic Languages and Literatures, George Washington University.

Recent Comments