The ‘Isaiah Bulla’ and the Putative Connection with Biblical Isaiah: 3.0

The ‘Isaiah Bulla’ and the Putative Connection with Biblical Isaiah: A Case Study in Propospography

By Christopher Rollston, George Washington University (rollston@gwu.edu)

The Old Hebrew bulla excavated by Dr. Eilat Mazar, and published in Biblical Archaeology Review (March-May 2018) in an article entitled _Is this the Prophet Isaiah’s Signature(pages 65-73, notes on page 92) is of much interest and certainly merits substantive and substantial discussion.

____

Prolegomenon. It is perhaps useful in this connection to reference certain components of the time-line, as things have developed fairly rapidly, and I’ve been trying to carve out a few hours during the past few days to discuss this interesting find (hence this third blog on the bulla). During the afternoon of February 21, 2018, I was contacted by National Geographic to provide my reflections on the press release about an article on the “Yesha’yahu Bulla, an article slated to be published online at midnight that evening. Thus, after clearing my desk some, and after reading closely the press release, I wrote up my brief reflections about the need for caution regarding the assumption that this bulla was made from a seal of Isaiah the Prophet. I sent this off to National Geographic within about two hours of the original request. Biblical Archaeology Review published their article (i.e., the editio princeps) on February 21, 2018, and various news-outlets, of course, subsequently released their articles, including National Geographic. A number of my statements were included in that story (https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2018/02/prophet-isaiah-jerusalem-seal-archaeology-bible/). I found the National Geographic story to be very useful, especially since most or all other news-outlets seem to have presumed that this bulla was probably (or was certainly) that of Isaiah the Prophet. Around 8:30 a.m. on February 22, 2018, prior to heading off to teach, I posted the full version of my comments to my blog (http://www.rollstonepigraphy.com/?p=796), in which I mentioned (as I had to National Geographic) my core concerns, namely, the root yš‘ is a very productive root for personal names (with around twenty people in the Hebrew Bible with names derived from that root, thus, revealing that there many people with the name “Isaiah,” or some similar name based on the same root, in Judah during any given time; as well as my concern about the absence of an alep (which is essential for understanding this to be the word for prophet); my concern about the presence of a presumed internal yod mater lectionis (in light of the dearth of internal matres lectionis in Hebrew inscriptions of the late 8th and early 7th centuries BCE and in light of the fact the Lachish Letter 3.20 does *not* have the mater); my concern about the absence of the article (as in the majority of occurrences in ancient Hebrew of the word “prophet,” it is linguistically definite); as well as a notation about the fact that there are a number of proper nouns in Hebrew that begin with the root letters nun and bet. Mazar’s article anticipated some of these criticisms, and her article uses the phrasing “may” be the bulla of Isaiah the Prophet, but the thrust of the article is about the prophetic figure. In any case, a day later, that is, at ca. 1:00 p.m. on February 23, 2018, I went live with a second post on this bulla, fleshing out some of my suggestions in my first blog (of February 22nd), including and especially the various possibilities for the letters nun, bet, yod (nby) of the third register (http://www.rollstonepigraphy.com/?p=801). Now, at this time (February 26, 2018), I here posting some additional details about this bulla, especially regarding the three letters on the third register, heavily incorporating data from my previous two blog posts. Note that this third blog post is the basis for a forthcoming article in a traditional publication venue (i.e., a print publication, rather than just a blog).

__

Discussion of Bulla

__

Material: Impressed Clay.

Condition of Bulla: Partially Broken.

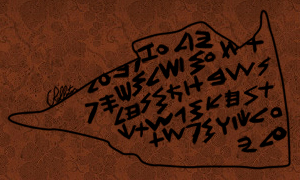

Reading of Bulla: First Register: Partially broken, fragmentary iconograhic element; Second Register: L-yš‘yh[w]; Third Register: nby. Note the absence of bn “son of” (but note that this morpheme is sometimes absent from patronymics in the epigraphic record).

Thus, the bulla reads “Yešayahu, nby”

NB: The word that follows the first personal name on a seal (and, thus, a bulla) is normally: a patronymic, a gentilic (descriptor), or a title.

__

Date: this inscription putatively dates to the 8th century or the early 7th century. That is, I would emphasize that the script is the script of the late 8th or early 7th century BCE, and there is no way to be more precise than that. And, of course, the archaeological context is not such that the date can be stated to be only the 8th century. Ultimately, a date in the late 8th century is permissible, but so is a date in the early 7th century.

__

Potential Problems with understanding nby on the third register as prophet, that is, potential problems with assuming that the third register is to be understood as reading: nby[’]:

The fact that an alep is not present, or preserved, after the yod is of critical importance. Without it, we do not have the word for prophet. With it, we would not be conversing about this…because if there were an alep there, then we would have the word prophet (or a verbal or nominative based on that same root). But, alas, we don’t have it, hence the necessity of this conversation (and I do not find it convincing to contend that because of the, especially later, quiescent nature of the alep, it simply wasn’t written on this bulla; after all, we have it present in many Iron Age inscriptions, including in the very word for prophet in Lachish 3:20). I have essentially noted all of this previously but also emphasize it here as a point of departure. Ultimately, this entire conversation (about wanting to read the word prophet here, even though we don’t have a critically important letter that must be present to make the case with certainty), reminds me of the previous attempts to contend that he broken Hebrew seal with the letters “yzbl” must refer to Queen Jezebel (I deal with those analogous assumptions in an article entitled “Prosopography and the YZBL Seal” in IEJ 59 [2009]: 86-91). That’s not the only possible reading of that seal; similarly, reading “prophet” on this bulla is not the only possible reading here.

Furthermore, the preponderance of the occurrences of the word for prophet are definite (either via the usage of the article, or via the presence of a pronominal suffix, or in a construct chain in which the nomen rectum is definite). I have noted all of this in the previous posts, but emphasize it here as well. And it is also worth emphasizing that the epigraphic occurrence of the word prophet (h-nb’) in Lachish 3:20 conforms with this pattern. In any case, as I have noted, the absence of the article here does not mean that this word cannot be the word for prophet, but it merits attention nonetheless, as it is concerning. Furthermore, after noticing that Eilat Mazar’s article suggests (e.g., in the accompanying drawing) that the article (i.e., the hey) could be reconstructed at the end of the preceding line, I would emphasize that I find that very, very difficult to accept. There is simply no room at the end of the previous line for that letter (note that the Old Hebrew letter hey normally takes up a fair amount of horizontal space). Anat Mendel-Geberovich has indicated to me that she also believes that there is not sufficient space for the letter hey at the end of the preceding line.

Moreover, as I mentioned in the previous blog posts, if this word on the bulla is the word “prophet” (i.e, if someone were to assume that the alep were really present and that we have the word for prophet), the presence of a yod mater lectionis is thus different from the attested spelling of this word in epigraphic Hebrew, namely, Lachish Letter 3, line twenty (an inscription that dates to the early 6th century, a time period during which we see even more internal matres lections). ). Moreover, as I also mentioned in my previous posts, although we do have internal matres lectionis in Old Hebrew inscriptions, beginning in the late eighth century, it is rare (for discussion and bibliography, see “Scribal Education in Ancient Israel: The Old Hebrew Epigraphic Evidence.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 344 [2006]: 47-74, especially pages 61-66). Ultimately, because we do not have the yod in the Lachish Ostracon, it could be suggested that this weakens the case for this being the word prophet in this new bulla (and, as noted, the absence of the alep is a major obstacle).

Or again, as I have mentioned in my previous posts, it is also the case that the Hebrew names are based on Hebrew roots, of course, and the root yš‘ (yod, shin, ‘ayin) is the basis not just for the name of Isaiah the prophet, but for almost twenty different people in the Bible (from various periods). And this name persists deeply into the Second Temple Period as well, with at least a dozen attestations (see, for example, Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity, Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck, 2002, p. 180). Thus, during any given period, there were likely a number of people running around in Judah, and the city of Jerusalem, who had the name Isaiah (or a form thereof, based on the same Hebrew root).

__

Nevertheless, it seems that in spite of the absence of the critically important alep (etc.), and in spite of the absence of an article, the presence of the yod, and the prevalence of the PN “Isaiah,” some have contended that this bulla is that (or most likely that) of the prophet Isaiah. And most have argued this because they believe that about the only reasonable understanding of the letters nby is to restore an alep and read the word “prophet.”

__

Before proceeding, I would emphasize (and reiterate) in this connection that those proposing this are presupposing the yod is an internal mater lectionis and that there is sufficient space after the yod for an additional letter.

__

It is useful, therefore, for me to reference again (while also augmenting my previous posts at times) some of the various additional possibilities that must be considered for nby. Here are a few options:

(1) The name Nbyt (attested as a personal name, often contended to be a gentilic of sorts, in Genesis 25:13). Such a proposal would suggest that the yod is an internal mater lectionis and that there is sufficient space after the yod for an additional letter. In this case, the word would arguably be a patronymic.

(2) The name Nbṭ (i.e, with the final consonant a ṭet). This personal name is attested within the Hebrew Bible (e.g. 1 Kgs 11:26) as well as in Old South Arabic personal names (see (see M. Noth, Die israelitischen Personennamen im Rahmen der gemeinsemitischen Namengebung, Beiträge zur Wissenschaft vom Alten und Neuen Testament, III, 10. Stuttgart, 1928 [reprint: Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1966], pages 36, 186). This name seems to be based on a root that means “bring to light.” Such a proposal (i.e., for this word) would suggest that the yod is an internal mater lectionis and that there is sufficient space after the yod for an additional letter (note that although the formation in the Bible is based on this root, the form on the bulla would need to reflect a different formation so as to account for the yod as a mater lectionis; thus, in this case, one could posit a qattîl or a qātîl. For these formations, see Bruce K. Waltke and M. O’Connor, Biblical Hebrew Syntax, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1990, section 5.4, page 89). In this case, the word would arguably be a patronymic (as in the previous case).

(3) The name Nabil is also something that is plausible, a name that arguably has a core semantic domain of meanings such as “noble,” “wise,” “light,” or “flame.” This proposal would suggest that there is room for a letter after the bulla’s yod. Note that there is, of course, a very famous pun (cf. the phenomenon of nominal pejorative equivoces) in the Bible (1 Sam 25:25) on a personal name “Nabal” (I dealt with this name in “Ad Nomen Argumenta: Personal Names as Pejorative Puns in Ancient Texts,” in the volume entitled In the Shadow of Bezalel: Aramaic, Biblical, and Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Bezalel Porten, ed. Alejandro F. Botta. Leiden: Brill, 2013, pages 367-386; in that article I follow James Barr, with regard to this personal name). In the case of this personal name, (especially) the qattîl formation or (perhaps) the qātîl formulation, would arguably account for a yod mater lectionis (Bruce K. Waltke and M. O’Connor, Biblical Hebrew Syntax, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1990, section 5.4, page 89). In this case, the word would arguably be a patronymic (as in the previous cases).

(4) The root Nbz. This word is attested in Imperial Aramaic (see Hoftijzer and Jongeling, Dictionary of the Northwest-Semitic Inscriptions, Leiden: Brill, sv Nbz) and seems to mean something such as “document,” “receipt.” In this case, as with the previous possibilities, it would be presupposed that there is room after the yod of the bulla for an additional letter, and in the case of this word, the yod would be understood as a mater lectionis, and the word could be understood as a title, something such as “recorder” (on the subject of foreign words and loan words in Northwest Semitic, see works such as Stephen A. Kaufman, The Akkadian Influences on Aramaic (Assyriological Studies 19), Chicago: University of Chicago 1974; Paul V. Mankowski, Akkadian Loanwords in Biblical Hebrew, Harvard Semitic Studies 47, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2000). Of course, in the case of a title, I would also prefer for there to be a definite article (hey), since we often get it with titles. But since some are willing to propose that the article is not necessary before the word “prophet,” then I think it is also fair to state that it could be nbz as a title (or, less likely, a personal name), with a yod mater (and someone could propose that it follows a formation such as a qattîl or a qātîl. For these formations, see again Bruce K. Waltke and M. O’Connor, Biblical Hebrew Syntax, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1990, section 5.4, page 89). I should emphasize that I might in this case contend that the title could have entered Hebrew through Akkadian (something that would not be sui generis in Hebrew, of course). Ultimately, I do not think that this would be the most compelling restoration (i.e., of a zayin), but, again, there is a remote possibility, depending on the kind of formation that someone might propose.

(5) There are a number of personal names (in various languages, including Hebrew) that are built upon the theorphic element Nb- (i.e, the God Nabu). It is possible that the bulla’s nb is this theophoric element, but space constraints would perhaps militate against this (as the non-theophoric component would require at least two or three letters and there is not sufficient space for that), as would perhaps also a putative Judean having such a name in the late 8th century or early 7th century, as would perhaps also, of course, the presence of a yod on the bulla (but…the yod might not be a problem, if, for example, it were part of a verbal or nominal modifier). Of course, the spelling of this DN would normally include a waw. Note also in this connection that double names are a well-known phenomenon in the Semitic world, as well as later in the Greco-Roman world (and thus one could conceivably argue that the first name is the Hebrew name and the second name is an Akkadian name for the same person; cf. of course, later cases such as Hadassah = Esther; Daniel = Belteshazzar; Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah = Shadrack, Meshach, Abednego [Abednebo[; Saul = Paul, etc.). Again, I am disinclined to embrace this possibility, but it is theoretically possible.

(6) The GN (geographic noun) “Nob” comes readily to mind and this famous biblical GN (e.g., 1 Sam 21:2, et passim) is one of those I had in mind in my initial post with my reference to proper-noun possibilities (hence the choice of the term proper “noun” rather than “personal name” in that initial post). In this case, it might be possible to contend that the word Nby of the bulla is a gentilic, meaning something such as “Nobite.” Moreover, Lawson Younger has indeed suggested that understanding Nby as a gentilic (e.g., “Nobite,” and thus “Isaiah the Nobite”) is something he considers quite appealing; and Nathaniel Greene has independently indicated to me that he is inclined to view it this way. Furthermore, Nadav Na’aman has independently indicated to me that he embraces this understanding, and he has noted the name Nobay (Nobite) in Nehemiah 10:20 (cf. also the spelling in LXX). And Younger, Greene, and Na’aman have (cumulatively) also referenced three seals from the antiquities market in this regard and one from Lachish (see Nahman Avigad and Benjamin Sass, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1997, #379; #227; #693; and from an excavation, #530 [Lachish]). Of these, I would emphasize that #530 is from an excavation and so it is the one that can best carry the weight, that is, be considered the best evidence for the presence of this reading in the epigraphic record. In addition Na’aman has drawn my attention to H. Rechenmacher’s Althebraische Personennamen, Munster 2012, 179. In this case, “Nobite” would be a gentilic (rather than a patronymic or a title). Obviously, in this case the yod could be viewed as a final mater (and these are nicely attested as early as the late 9th and early 8th centuries BCE), but, as P. Kyle McCarter has emphasized (personal communication) the yod probably represents -at, only later developing to final î. Furthermore, as Kyle McCarter has also emphasized, if this is a straightforward gentilic, we would also want the article here “the Nobay,” “the Nobite.” Thus, McCarter has indicated that his preference is to understand this as an original gentilic (ay) which had become a personal name (as also with the father of Zephaniah, “Cushi”, Zeph 1:1), thus, yielding for this bulla a standard patronymic, “Isaiah (son of) Nobay.” And because the father of the prophet Isaiah’s is named “Amoz” (Isa 1:1), this is clearly not a bulla of Isaiah the prophet (cf. the #379, from the market, which does have bn before nby).

And the elegance of this is that there is no presumption that there is a letter after the yod and there is no need to resort to an internal matres lectionis to account for the yod. Note in this connection that Lawrence Mykytiuk has indeed mentioned to me the fact that he is not convinced there is enough space for a letter after the yod. I have similar concerns.

(7) Within the corpus of ancient Hebrew (biblical and epigraphic), a final yod (or alep) can function as a hypocoristic element (with the hypocoristic signifying a DN). This yod was arguably consonantal at first, rather than being a pure mater lectionis. As for the final yod, note, gor example, ’ḥzy (Reisner Samaria Ostracon 25:3; meaning something such as “DN has seized”), bgy (EnGedi 2:6; arguably meaning something such as “DN has enriched,” so F.W. Dobbs-Allsopp J.J. M. Roberts, C.L. Seow, R.E. Whitaker, Hebrew Inscriptions, New Haven: Yale, 2005, 596), m‘šy (Arad 22:4; meaning something such as “work of DN”), ‘wpy (Jer 40:8; Khirbet el-Qom), šby (Yavneh Yam 1, end of line 7 and beginning of 8, meaning something such as “DN has returned”), and bqy (1 Chr 5:31; 6:36; an ostracon from Jerusalem, arguably from a geminate root or a medial w/y root). In addition, reference can also be made to ḥgy (Gen 46:16; Numb 26:15; and with epigraphic attestations, for example, in Hebrew, Phoenician, Old South Arabic, as well as later Arabic, and often understood to be a way of referring to someone who was born on a festal day), and also yš‘y (1 Chr 2:31, et passim; this being arguably a shortened form of yš‘yhw, but note also the Phoenician form of this personal name with an alep hyporistic and thus certainly not a Yahwistic theophoric). Thus, with that evidence in mind, and now as for the bulla’s third register reading of nby, it is useful to note that there is a Northwest Semitic geminate root nbb (also attested in the Bible, but with some etymologies that might not necessarily yield a great personal name), a Northwest Semitic middle waw root (attested in the Bible and the epigraphic corpus with the meaning “prosper,” or “rain abundantly,” and so something that would yield a good personal name), and a Northwest Semitic middle yod root meaning “fruit,” “give fruit” (and thus something that would yield a good personal name; cf. Isa 57:19, et passim; cf. also Mal 1:12). And, furthermore, it is possible that this putative gentilic in Neh 10:20 is actually to be connected with this root. In this case, the yod of the bulla’s nby (and thus also the Bible’s) would be a hypocoristic; and in this case there would be no need to restore a letter after the yod, and there is no need to resort to understanding the yod as an internal mater lectionis (something that, as noted, is difficult to have so early, as they are so rare in the late 8th or early 7th century). And, of course, as noted, the latter two roots mentioned in this paragraph would yield good personal names. The elegance of numbers 6 and 7 (in terms of not needing to resort to any special pleading) is particularly attractive. And, of course, in this case, the second name is a patronymic (cf. #379, from the market, which does have bn before nby). And because the name of the father of the prophet Isaiah is given as “Amoz” (Isa 1:1) this is clearly not a bulla of Isaiah the prophet.

(8) Furthermore, if one were to contend that the middle waw or middle yod root above is the operative one in this name, one could also argue (if someone believed that there was room after the yod for an additional letter) that the yod of the bulla is actually followed by a hey (although that would not necessarily be required) and that this is a PN (based on the middle waw or middle yod roots) and it is to be understood as something such as “Yahweh has given fruit” or “Yahweh has granted abundantly.”

(9) And there are additional options (e.g., a 1cs pronominal suffix on a verbal or nominal consisting of nb), which I will discuss in the print version of the article on this bulla (including, for the sake of thoroughness, discussion of the p > b phenomenon that is attested in epigraphic Old Hebrew, among other places). I do not think that this is operative in the case of the bulla, but it would open additional linguistic possibilities (including various personal names, such as biblical npyš).

___

Ultimately, the conclusion is that there are a number of different possibilities for the second word of this inscription. I have listed some of them here, and there are at least five to seven additional ones that could be listed. The “take away” is this. I would like to be able to say that this bulla is that of the prophet Isaiah, but that’s not at all the sole possibility, and although some of the suggestions here (above) are more likely than others (I have a slight methodological preference for options six and seven, as they do not require the positing of an internal mater lectionis and they do not require the addition of a letter after the yod, something which may be important in light of the apparent space constraints), it is certainly not the case that one can weight them in such a fashion as to affirm or declare that this or that one is *the* most likely. Some are more probable than others, but that’s about as far as good methodology allows us to go. And so the reading nby’ (“prophet”) will remain one of a number of various possibilities. Some will want certainly want “prophet” (nby[y]) to be *the* correct restoration (or understanding), but in light of the various alternatives, that is a very subjective opinion. And it’s important to be forthright about stating this. Alas, ultimately, we must always attempt to reflect deeply and broadly on restorations and readings. And in the case of this bulla, I think that there are a number of additional options and there is no empirical method of making a decisive determination.

Final Reflections on Broader Themes: It is perhaps useful to emphasize an additional, important facet of all such finds: we as a field are best served, of course, by always being vigilant and careful in the wake of a new archaeological or epigraphic find. Indeed, Carol Meyers and Eric Meyers felt this so strongly (in the wake of the Talpiyot Tomb media blitz) that they convened a symposium at Duke University in April 2009, and the volume entitled Archaeology, Bible, Politics, and the Media (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2012), was published on the basis of the lectures given at that symposium. Within my lecture at that symposium and my article in the volume (“An Ancient Medium in the Modern Media: Sagas of Semitic Inscriptions,” pages 123-136), I recount a number of occasions during the past fifty years in which there was a fair amount of distance between the early sensational claims made about various finds and the cold, hard historical and philological reality, namely, that the finds were, in fact, very nice finds, but fairly standard and mundane in terms of actual content and significance. I would like to reiterate here some of my concluding thoughts at the end of that article in the Meyers and Meyers volume: (1) “Scholars who interface with the media must always strive to be circumspect and intentional…searching for critiques of conclusions rather than just collegial confirmation”; (2) “Scholars must always remember that epigraphic finds are rarely as ‘dramatically important,’ ‘sensational,’ or ‘stunning’ as they might seem at first blush”; (3) “‘Gale-force winds’ often develop when inscriptions are discovered and the media typically want rapid and decisive comment, especially if the find putatively connects with something that is important biblically, religiously, or politically. Scholars should remind the media that the best constructs of the data are usually the result of a slow, methodical, scholarly process…” (p. 133); (4) Long ago, Max Miller emphasized to me that after some misunderstanding gets out in the public or scholarly world (and he was referencing especially things such as a mislabeling of a site on a biblical map), it becomes virtually impossible to excise. (5) In sum, methodological caution and methodological rigor are always “desiderata.”

Christopher Rollston, George Washington University (rollston@gwu.edu).

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to P. Kyle McCarter, Jr., Nadav Na’aman, Jason Bembry, Joel Burnett, Larry Mykytiuk, Nathaniel Greene, Anat Mendel-Geberovich, and Lawson Younger for discussing matters related to this bulla with me.

Recent Comments