BELIEF IN THE RESURRECTION IN ANCIENT CONTEXT

BELIEF IN THE RESURRECTION IN ANCIENT CONTEXT:

LATE SECOND TEMPLE JUDAISM, EARLY POST-BIBLICAL JUDAISM, AND EARLY CHRISTIANITY

There is often a great deal of misunderstanding about this subject generally. That is, people who do not work in ancient history or ancient religion often assume that a belief in a resurrection was some sort of distinctively Christian belief. That, however, is a serious misconception. The fact of the matter is that within various segments of Late Second Temple Judaism, as well as within Early Post-Biblical Judaism, the notion of a resurrection was warmly embraced by many. The locus classicus in the Hebrew Bible is arguably the following text from the mid-2nd century BCE: “Many of those sleeping in the dust of the earth shall awaken, some to everlasting life and some to everlasting peril” (Dan 12:2; notice here that the correlative of “damnation” or “hell” is also present in some fashion, of course). Within the Old Testament Apocrypha, the notion of a resurrection is embraced at times as well, with the narrative about the martyrdom of “the mother and her seven sons” being a fine exemplar of this. Thus, according to the narrative, one of the sons said during the torture that preceded his death: “the King of the universe will raise us up to an everlasting renewal of life, because we have died for his laws” (2 Macc 7:9). Similarly, the mother herself says within the narrative, as an exhortation to her martyred sons: “the Creator of the world…will in his mercy give life and breath back to you again” (2 Macc 7:23). 2 Maccabees arguably hails from the first half of the 1st century BCE. Regarding the dead, the Wisdom of Solomon also affirms that the dead “seemed to have died,” but “they are at peace,” and “their hope is full of immortality,” and they will ultimately “shine forth” and “will govern nations and ruler over peoples” (Wisdom 3:2-8 passim, with the Greek future tense being used here). The Wisdom of Solomon arguably hails from the second half of the 1st century BCE. Significantly, all of these texts antedate the rise of Christianity and they all affirm a belief in a resurrection. In short, many Jewish people believed in a resurrection long before Christianity came along. To be sure, a belief in a resurrection was not universally accepted by all Jewish people in the Second Temple period. Some Jewish people did not believe in a resurrection. For example, the traditionalist Ben Sira rejected the notion of eternal bliss for the righteous and eternal punishment for the wicked. Thus, he wrote: “Who in the netherworld can glorify the Most High, in place of the living who offer their praise? No more can the dead give praise than those who have never lived; they glorify the Lord who are alive and well” (Sir 17:27-28). In sum, although not all Jewish people of the Late Second Temple period accepted the notion of a resurrection, there are texts from this period that demonstrate that a fair number did.

Furthermore, the Jewish historian Josephus (lived ca. 37-100 CE) also discusses the subject of the perishability and imperishability of the soul, with regard to some of the major strands of Judaism during the first century of the Common Era. Regarding the Pharisees, therefore, he states that they believe “every soul is imperishable, but the soul of the good alone passes into another body, while the souls of the wicked suffer eternal punishment.” Conversely, regarding the Sadducees he states that “as for the persistence of the soul after death, penalties in the underworld, and rewards; they will have none of them.” Regarding the Essenes, Josephus states that they believe “the body is corruptible and its constituent matter impermanent, but that the soul is immortal and imperishable…sharing the belief of the sons of Greece, they maintain that for virtuous souls there is reserved an abode beyond the ocean, a place which is not oppressed by rain or snow or heat, but is refreshed by the ever gentle breath of the west wind coming in from ocean, while they relegate base souls to a murky and tempestuous dungeon, big with never-ending punishments” (Josephus, Jewish War, II, 11-14; for more discussion, see Nickelsburg 1972, 164-169). Of course, pericopes within the Greek New Testament regarding the Pharisees and Sadducees dovetail nicely with Josephus. The locus classicus for the New Testament is arguably contained within the book of Acts: “The Sadducees say that there is no resurrection, or angel, or spirit; but the Pharisees acknowledge all three” (Acts 23:8; cf. also Matt 22:23). Of course, within Early Christianity, the notion of a resurrection (and the presumed correlative, “hell”, is also attested in some form in Daniel 12:2) predominates, as the soil from which Christianity especially hails is that of apocalyptic Late Second Temple Judaism (Ehrman 1999). Pericopes within the Greek New Testament such as “The Rich Man and Lazarus” (Luke 16:19-31) and “The New Heaven and New Earth” (Rev 21) reflect this, of course. Moreover, the belief in a resurrection persists in subsequent chronological horizons of Early Christianity as well (e.g., see Ferguson 1999, 16,23, 26, 65-78).

In short, based on evidence from literary texts associated with Late Second Temple Judaism and Early Christianity, scholars of the Hebrew Bible, Second Temple Judaism, the Greek New Testament, and Early Christianity have for a very long time dealt with these ancient assumptions about the afterlife; therefore, the consensus of the field has long been that some Jewish people within the Late Second Temple period embraced a belief in a resurrection and some did not (e.g., DiLella 1966; Collins 1998; Ehrman 1999). Of course, Christianity too (originally a sect of Judaism, with strong apocalyptic tendencies) did embrace a notion of a resurrection, and this is very clear from the documents of the Greek New Testament. But the fact remains that many Jewish people of the late Second Temple Period believed in a resurrection, not just Jewish Christians, and the fact remains that a belief in the resurrection is attested within Judaism prior to the rise of Christianity. This is just a historical fact.

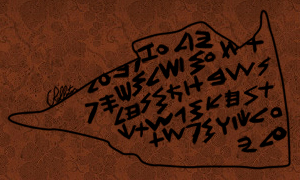

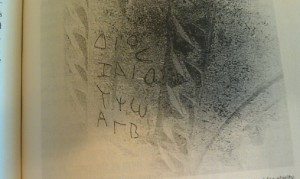

Significantly, for Late Second Temple Judaism and Post-Biblical Judaism, epigraphic evidence also demonstrates that some Jewish people believed in a resurrection and some did not. For example, an inscription in a corridor of the Jewish catacombs of Beth She’arim reads as follows: “Best wishes in the Resurrection!” (Greek: “anastasis”; Schwabe and Lifschitz 1974, 180 [#194]). Moreover, one ossuary from Jerusalem has the following: “No one has abolished/cancelled his entering, not even El‘azar and Shapira” (CIIP 1. #93). Similarly, a Jerusalem ossuary has the following Greek inscription: “Cheer up and feast, you brothers who are living, and drink together! No one is immortal” (CIIP 1. #395). Similarly, an inscription in a mausoleum adjacent to catacomb eleven at Beth She’arim has the following inscription: “I, the son of Leontios, lie dead, Justus, the son of Sappho, who, having plucked the fruit of all wisdom, left the light, my poor parents in endless mourning, and my brothers too, alas, in my Beth She‘arim, And having gone to Hades, I Justus, lie here with many of my own kindred, since mighty Fate so willed. Be of good courage, Justus, no one is immortal” (Schwabe and Lifschitz 1974, 97 [#127]). Similarly, an inscription from Beth She’arim reads: “Be of good courage, Simon; no one is immortal” (Schwabe and Lifschitz 1974, 35-36 [#59]). Or again from Beth She’arim: “Be of good courage, lady Calliope from Byblos; no one is immortal” (Schwabe and Lifschitz 1974, 124-125 [#136]). From a Greek inscription from Beth She’arim: “May your portion be good, my lord father and lady mother, and may your souls be bound in immortal life” (Greek: athanatou biou; Schwabe and Lifschitz 1974, 114-116 [#130]). Among the longest of this sort of inscription from Beth She’arim is the following: “this tomb contains the dwindling remains of noble Karteria, preserving forever her illustrious memory. Zenobia brought her here for burial, fulfilling thus her mother’s behest. For you, most blessed of women, your offspring, whom you bore from your gentle womb, your pious daughter, for she always does actions praiseworthy in the eyes of mortals, erected this monument so that even after the end of life’s term, may you both enjoy again indestructible riches” (Schwabe and Lifschitz 1974, 157-167 [#183]). Similarly, an inscription from Beth She’arim says: “May your lot be good, Hannah” (Schwabe and Lifschitz 1974, 2-3 [#2]). Or again, one of the Beth She’arim inscriptions contains the following statement: “Julianus Gemellus, may your share be good” (Schwabe and Lifschitz 1974, 8 [#13]). And again, “Sarah, mother of Yosi, have courage” (Schwabe and Lifschitz 1974, 16 [#22]). Likewise, an ossuary from Beth She’arim has the word “peace” in Greek and Hebrew and in its entirety it reads as follows: “Shalom, little Yosi, Shalom” (Schwabe and Lifschitz 1974, 19 [#28]). In sum, some epigraphic texts from ancient Judaism presuppose a belief in a resurrection and some do not.

Thus, in the final analysis, the cumulative evidence is decisive: There is nothing distinctively “Christian” about a belief in a resurrection. Rather, some segments of Late Second Temple and Early Post-Biblical Judaism believed in a resurrection and some segments did not. Christianity, as an heir to apocalyptic branches of Judaism, was quite consistent in always affirming a belief in a resurrection, but the fact remains that belief in a resurrection is well attested prior to the rise of Christianity, and this belief also persists in certain segments of Judaism after the rise of Christianity.

Christopher Rollston

CIIP 1

2010 Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae: volume I, Jerusalem, Part 1, 1-704. H. Cotton, L. Di Segni, W. Eck, B. Isaac, A. Kushnir-Stein, H. Misgav, J. Price, I. Roll, and A. Yardeni, eds. Berlin: DeGruyter.

Collins, J. J.

1998 The Apocalyptic Imagination: An Introduction to Jewish Apocalyptic Literature, 2nd ed.

Biblical Resource Series. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Di Lella, A. A.

1966 “Conservative and Progressive Theology: Sirach and Wisdom.” CBQ 28: 139-154.

Ehrman, Bart

1999 Jesus: Apocalpytic Prophet of the new Millennium. New York: Oxford.

Ferguson, E.

1999 Early Christians Speak: Faith and Life in the First Three Centuries. 3rd edition. Abilene:

Abilene Christian University Press.

Nickelsburg, G. W.E., Jr.

1972 Resurrection, Immortality, and Eternal Life in Intertestamental Judaism. Harvard

Theological Studies 26. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Schwabe, M. and Lifschitz, B.

1974. Beth She‘arim: Volume II, the Greek Inscriptions. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and the Institute of Archaeology of Hebrew University.

Recent Comments