Rollston on the Father Nazario Inscribed Stones, Puerto Rico

Through the years, I have often been asked by journalists and scholars about the Inscribed Stones from Puerto Rico, associated with Father Nazario. Several years ago, at the invitation of Dr. Reniel Rodriguez Ramos, I traveled to Puerto Rico to see most of the extant corpus and to collate some of the best exemplars. Here are my views of this very interesting corpus.

The Inscribed Stones of Father Nazario have been known since ca. 1890 (see Pinart 1890). According to Father Nazario, they putatively hail from the municipality of Guayanilla, on the southern coast of Puerto Rico. Originally, there were ca. 800 of these Nazario Inscribed Stones. Some 270 of these remain in the collection of the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture (San Juan). In addition, ca. 8 are part of the collection of the Museo Guayanilla (Puerto Rico); ca. 6 are part of the collection of the University of Puerto Rico; ca. 5 are part of the collection of the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History; ca. 5 are part of the collection of the Peabody Museum of Harvard; and ca. 37 are part of the collection of the Quay Branly Museum in Paris.

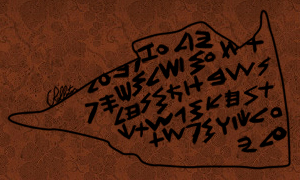

The Inscribed Stones have been worked and are anthropomorphic in form, although primitive in terms of workmanship. The preserved portions of these Inscribed Stones consist of a human head, replete with the facial features (e.g., nose, eyes, mouth, chin). These stones are also inscribed with features that are most readily understood as “signs” (hence the term “inscriptions” has been used in the past for this corpus). Often these stones have horizontal register lines. Moreover, on some of these stones, there are burn marks that post-date the shaping and inscribing. The surface of the stones is quite worn and abraded, and sometimes this makes it rather difficult to determine the precise original morphology of the signs.

Some have suggested during the past that these stones were shaped and inscribed in the modern period (i.e., that they are modern forgeries), including J. W. Fewkes (1903; 1907). There have also been some important dissenting voices in the past. For example, Professor R. P. Dougherty of Yale University was sent (on March 23, 1927 for analysis) two of the Nazario Inscribed Stones. Dougherty visually examined the Inscribed Stones and also brought into the discussion Charles Torrey (Chair of the Department of Semitic Studies at Yale at that time). Part of Dougherty’s reason for bringing Torrey in on the discussion was that some (including Father Nazario) had suggested that the signs on the Inscribed Stones were linear Northwest Semitic letters, either Hebrew or Phoenician. In a letter dated May 13, 1927 from Dougherty (to Alice L. de Santiago, the owner of the Inscribed Stones at that time), certain interesting things are mentioned. For example, Dougherty notes that he and Torrey “regard them as very interesting objects of authentic nature. That is, we do not regard them as fakes.” A line or two later, Dougherty states that he and Torrey feel that “they were not made recently as counterfeit antiquities.” As to the precise age, Dougherty does state (earlier in the letter) that “there is nothing by which a decision can be reached.” Also of import is the fact that in this letter Dougherty states that Torrey’s view is that “there are no Phoenician characters represented by any of the markings on the stones you sent.” In this connection, it is perhaps important to mention that Torrey was certainly capable of detecting forgeries in the Northwest Semitic corpus (for reference, Rollston 2013).

Because some have suggested that these Inscribed Stones are connected with the “Lost Tribes of Israel,” it is important to emphasize that the term “Lost Tribes of Israel” is a misnomer. That is, the tribes of the Northern Kingdom of Israel were not lost. After all, we know very well what happened to them, based on a constellation of data from antiquity. Namely, in the wake of the destruction of the Northern Kingdom of Israel (including its primary capital city of Samaria, or in Hebrew, “Shomeron”) in ca. 722 BCE by the Neo-Assyrian Kings Shalmaneser V (and his successor) Sagon II, two things occurred: (1) many Northern Israelites (i.e., people from the so-called ten Northern Tribes) were deported to locations within the broader Neo-Assyrian Empire (2) and various peoples who had previously been conquered by the Neo-Assyrians were imported into the region of the former Northern Kingdom of Israel. This sort of “deportation and importation” was standard Neo-Assyrian practice for conquered peoples. Moreover, both the Hebrew Bible and ancient Near Eastern inscriptions provide textual evidence for these two facets of the fate of the Northern Kingdom of Israel. Thus, within the biblical book of Kings, the following is stated” “Then the King of Assyria invaded all the land and came to Samaria; for three years he besieged it. In the ninth year of Hoshea (of Israel), the king of Assyria captured Samaria; he carried the Israelite away to Assyria. He placed them in Halah [a city Northeast of Nineveh], on the Habor, the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes” (2 Kgs 17:5-6). Subsequently, it is noted in the same chapter that “the king of Assyria brought people from Babylon Cuthah, Avva, Hamath, and Sepharvaim, and placed them in the cities of Samaria in place of the people of Israel; they took possession of Samaria and settled in its cities” (2 Kings 17:24; cf. also 2 Kings 18:9-11). The point is that the “tribes of Israel” were not “lost.” Rather, the book of 2 Kings notes that many of these people (i.e., the Northern Israelite tribes) were deported by the Neo-Assyrians to the region of Neo-Assyria and the land of the Medes (then under Neo-Assyrian hegemony) and the book of 2 Kings also notes that the Neo-Assyrians also imported into the region of the former Northern Kingdom of Israel various peoples from regions they (i.e., the Neo-Assyrians) had previously conquered. Of particular import is the fact that Neo-Assyrian historical texts describe things in the same basic manner as does the Bible (see Pritchard 1969, pp. 284-287). Various academic works have been written about this subject (e.g., Younger 1998; Becking 1992). In short, the Northern tribes were not “lost.” We know what happened to them (based on the texts cited above). Furthermore, the New Testament references to “the Samaritans” constitutes additional evidence for the continuation of the people of the old Northern tribes in the region (e.g., John 4; Matthew 10:5-6; Luke 9:51-53; Luke 2:36; see also Purvis 1968, etc.). For these sorts of reasons, any suggestion that the Northern Israelite tribes migrated to the Americas is absolutely contrary to the actual ancient evidence. In reality, all of the available ancient evidence demonstrates that these tribes remained in the ancient Near East. Thus, there are no “lost” tribes of Israel: the Bible and the ancient Near Eastern evidence make this clear.

At this time, it is useful for me to provide a basic description of the Nazario Inscribed Stones (based on my in-person analysis of some one-hundred of them) and then to discuss certain aspects of the writing. Among the most prominent features of many of these inscribed stones is a horizontal register line. The register line will sometimes be present on multiple sides of a stone. Sometimes the horizontal register lines will be intersected by a vertical line or a diagonal line. The intersection of the horizontal register line and the vertical (or diagonal) line will sometimes have the visual appearance of a cartouche. Sometimes one line of signs will be written in proximity to the register line (i.e., above it or below it), but sometimes two or three lines of signs will be written in proximity to the same horizontal register line. On a number of these inscribed stones, a portion of the surface of the stone has been incised with a decorative grid-pattern of intersecting lines.

The assemblage of signs of these inscribed stones cannot be readily identified with a known writing system. Because of the region from which they putatively hail, one might presuppose that these would be inscribed with a known Mesoamerican script, but this does not seem to be the case (e.g., it is not similar to Mayan or Aztec, etc.). Furthermore, since the time of the discovery of these stones, some have suggested that the signs on these stones are similar to linear Semitic alphabetic traditions (e.g., Phoenician, Hebrew, Aramaic, or their congeners such as Punic, Nabataean, Palmyrene, Epigraphic South Arabian, etc), but the assemblage of signs on the Nazario Inscribed Stones is not that of the Northwest Semitic alphabet.

To be sure, someone might wish to posit that there are some putative similarities between certain signs on the Inscribed Stones and the basic morphology of very simple Semitic letters. However, the presence (in the corpus of Nazario Incised Stones) of a closed or open circle (which is the basic morphology of an ‘ayin), or the presence of a fairly vertical line (which is the basic morphology of a nun in certain periods and script series), or the presence of something that resembles a circular or triangular form and a stem (which resembles a bet in certain periods) does not ultimately constitute good evidence that we are dealing with some sort of a variant of the Northwest Semitic linear alphabet. After all, the morphological similarities are superficial and the putative repertoire of constants in the Nazario Inscribed Stones is much too small to reflect anything approximating the Northwest Semitic linear alphabet. Of course, it is not impossible that the person or persons responsible for the signs on the Nazario Inscribed Stones had seen some alphabetic script, but I am not inclined to posit even this. In any case, on these Nazario Inscribed Stones, we certainly do not have some variant of the assemblage of signs of the Semitic alphabet, nor of the Greek or Latin alphabets. This was Torrey’s basic conclusion and it is mine as well.

As part of placing the Inscribed Stones in the broader context of writing (for a summary of writing in the ancient Near East, see Rollston 2019), it is perhaps useful for me to mention here that an alphabetic writing system can be defined as a system of writing in which each grapheme represents a single phoneme in the language (with the word “’phoneme” being defined as the smallest meaningful unit of sound in a language). In alphabetic writing systems, there are normally some twenty to forty graphemes (i.e., “letters”). Sometimes alphabetic writing systems represent only consonants (as in Iron Age Phoenician), sometimes consonants and vowels are both represented rather fully (e.g., ancient Greek and Latin) and sometimes an alphabetic writing system will represent consonants and some of the vowels (e.g., the marking of certain long vowels in ancient Aramaic and Hebrew). Within ancient alphabetic writing systems, therefore, the writing system is a graphic system of representing the sounds of the spoken language. Alphabetic writing is first attested ca. 1800 BCE. Note that Mesopotamian cuneiform and Egyptian Hieroglyphics (and Hieratic and Demotic) are non-alphabetic writing systems. For these writing systems, the earliest representations are pictographic in nature. Egyptian Hieroglyphics continued to be pictographic throughout its long history of usage, but Egyptian Hieratic and Demotic were much less so. The earliest writing in Mesopotamia was non-alphabetic and pictographic, but the pictographic nature of the script was soon lost (especially because clay was the standard medium and the standard tool used to write in the clay produced a wedge-shaped sign, hence, the term “cuneiform,” that is, “wedge-shaped,” and thus not something very capable of preserving a pictographic nature). Within these non-alphabetic writing systems, a sign can represent an entire word (these are called logograms), syllables (these are called syllabograms), and determinatives (a determinative is a sign that describes the noun which it is modifying). Non-alphabetic writing is first attested ca. 3200 BCE. The number of signs in a sophisticated and fully-developed non-alphabetic writing system is usually a few hundred. It is normally quite easy to be able to determine if a writing system is alphabetic or non-alphabetic.

Now, as for the Inscribed Stones of Father Nazario, the frequent repetition of certain signs (in immediate or close succession) and the small number of signs used in any given sequence strongly suggests that we are not dealing with an alphabetic writing system. Moreover, it is also particularly clear that we are not dealing with some sort of a complex non-alphabetic writing system (i.e., a system with logograms, syllabograms, and determinatives). After all, the number of attested signs on the Inscribed Stones is not even remotely close to that of complex non-alphabetic writing systems. Nor also does it seem convincing to suggest that we are dealing with a syllabary (as there are simply not even close to enough different signs represented for such a position to be tenable). However, the fact that we do have register lines, and the fact that we do have some consistency with regard to the morphology of certain signs is interesting, and this suggests that those responsible for these Inscribed Stones were attempting to communicate in some sort of simple symbols of fledgling writing system (perhaps within a small guild of practitioners).

Ultimately, as for the Nazario Inscribed Stones, it seems reasonable to posit that in terms of classification, we are dealing with something that could be described as emergent writing or a fledgling system of symbols or signs. Furthermore, it seems to me to be reasonable to posit that stimulus diffusion was part of the raison d’etre for the signs on the Nazario Inscribed Stones. That is, those attempting to write upon these stones knew about (or had seen), writing (perhaps that in use in Mesoamerica at the time), but for some reason they did not attempt to replicate the signs or the symbols of that writing system.

In sum, I am not inclined to consider the Nazario Inscribed Stones to be modern forgeries. I have worked on the subject of epigraphic forgeries for some time, and I have worked with and debunked a number of modern forgeries (e.g., Rollston 2003; Rollston 2004; Rollston 2005). Of course, there were epigraphic forgeries that surfaced on the market during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and before and after that era (Rollston 2014 and literature cited there), but the Nazrio Inscribed Stones strike me as quite different from these.

Select Bibliography

Becking, Bob. 1992 The Fall of Samaria: An Historical and Archaeological Study. Leiden: Brill.

Fewkes, J. W. 1903 Field Notes, April 13 and 14, 1903. National Museum of Natural History, Washington D.C.

Fewkes, J.S. 1907 The Aborigines of Porto Rico and Neighboring Islands, Government Printing Office, Washington D.C.

Pinart, Alphonse

1890 Notas sobre los petroglifos y antigüedades de las Antillas Mayores y Menores. Translated by M. Cardenas. Reprinted from Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology for 1888-1889, pp. 136-137. Boletín de la Academia Puertorriqueña de la Historia VI(24): 229-258.

Pritchard, James B.

1969 Ancient Near Eastern Texts relating to the Old Testament. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Purvis, James D.

1968 The Samaritan Pentateuch and the Origins of the Samaritan Sect. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rollston, Christopher.

2003 “Non-Provenanced Epigraphs I: Pillaged Antiquities, Northwest Semitic Forgeries, and Protocols for Laboratory Tests.” Maarav 10 (2003): 135- 193.

Rollston, Christopher.

2004 “Non-Provenanced Epigraphs II: The Status of Non-Provenanced Epigraphs within the Broader Corpus of Northwest Semitic.” Maarav 11 (2004): 57-79.

Rollston, Christopher. 2005 “Navigating the Epigraphic Storm: A Palaeographer Reflects on Inscriptions from the Market.” Near Eastern Archaeology 68 (2005): 69-72.

Rollston, Christopher. 2013 “Chapters in the History of Modern Forgery: Professors Leopold Messerschmidt and Charles Torrey on a Hebrew Inscription.” URL: https://www.rollstonepigraphy.com/?p=618.

Rollston, Christopher. “Forging History: From Antiquity to the Modern Period.” Pp. 176-197 in Archaeologies of Text: Archaeology, Technology, and Ethics, eds. Matthew Rutz and Morag Kersel. Joukowsky Institute Publication Series of Brown University, Oxbow Books.

Rollston, Christopher. 2019 “The Alphabet Comes of Age: The Social Context of Alphabetic Writing in the First Millennium BCE.” Pp. 371-390 in The Social Archaeology of the Levant: From Prehistory to the Present, eds. Assaf Yasur-Landau, Eric Cline, and Yorke Rowan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Younger, K. Lawson, Jr. 1998 “The Deportations of the Israelites.” Journal of Biblical Literature 117: 201-227

No Comments to “Rollston on the Father Nazario Inscribed Stones, Puerto Rico”