The Jesus Family Tomb

Prosopography and the Talpiyot Yeshua Family Tomb: Pensées of a Palaeographer

I. Foundational Considerations

The field of prosopography is broad, but it can be described as a field that attempts to reconstruct and describe data revolving around the subjects of genealogy, onomastics, and demographics.[1] Within the field of prosopography of antiquity, there is often a predominant focus on the status, vocations, and consanguinity of elites (because a substantial portion of the epigraphic data derived from elite circles and activities). For certain fields of ancient prosopography (e.g., Northwest Semitic epigraphy), prosopographic analyses will also include attempts to argue for (or against) the identification of a person attested in a literary corpus (e.g., the Hebrew Bible) with someone attested in the epigraphic corpus. Although certitude is the desideratum in the field of prosopography, it is often difficult to achieve, based on extant data.

The most reliable prosopographies are those based on a convergence of epigraphic, archaeological, and (when available) literary data. However, certain minimal controls are mandatory for such analyses to be convincing or even tenable. The patronymic (“son of” of “daughter of”) is a most fundamental component for prosopographic analyses. For the ancients, this was a means of differentiating (to some degree) people with the same name; therefore, patronymics are very common in the epigraphic corpus. For modern prosopographic analyses, such data are critical.

Sometimes there will be a personal name and a patronymic in an epigraphic source, but without further (or more substantive) reference in the epigraphic corpus and also without a potential reference in a literary source. For example, the Aramaic Samaria Papyri refer to a slave named Yehohanan bar She’ilah.[2] Within the corpus of Aramaic and Hebrew inscriptions from Masada, there is reference to a certain Shimeon bar Yehosep and a certain Shimeon ben Yo’ezer.[3] A Jerusalem ossuary is inscribed with the following Greek inscription: “Alexas Mara, mother of Judas Simon, her son.”[4] However, because complementary data are not present, nothing more can be said about any of these personal names. This is the case for many of the personal names in the epigraphic corpus.

Nevertheless, sometimes complementary and converging data are present in the epigraphic corpus. For example, during Yohanan Aharoni’s excavations at Arad, several Old Hebrew seals were discovered in Arad VI-VII with the personal name ‘Elyashib and the patronymic ben ‘Ishyahu. A number of Old Hebrew ostraca were also discovered in Arad VI-VII, and some of these ostraca also refer to a certain ‘Elyashib.” Based on the archaeological context of the seals and ostraca, it can be argued with substantial certitude that the ‘Elyashib of the ostraca is the same person as the ‘Elyashib ben ‘Ishyahu of the Old Hebrew seals. Moreover, based on the convergence of the Old Hebrew epigraphic data from the seals and the ostraca, it can be stated that ‘Elyashib ben ‘Ishyahu was a senior military commander at the Arad VI-VII fortress, with a multitude of described responsibilities and activities.[5] This sort of data is the essence of prosopographic analysis.

Sometimes, there is sufficient data to posit that a figure attested in the epigraphic corpus and a figure attested in a literary corpus are probably the same. This can be very useful for prosopographic analysis, although certitude is often evasive. For example, during Yigal Shiloh’s excavations at the City of David, a number of bullae were discovered in stratum X, a stratum that was destroyed by the Babylonians in ca. 587 B.C.E. Bulla 2 reads: “Belonging to Gemaryahu ben Shaphan.” Shiloh posited that the Gemaryahu of this bulla is to be identified with “Gemaryahu son of Shaphan the scribe” who is mentioned in a biblical text (Jer 36:10 et passim), a figure during the reign of Jehoiakim (r. 609-598 B.C.E.).[6] Within the editio princeps of this corpus of bullae, Yair Shoham reiterated Shiloh’s basic affirmation, but also noted a caveat: “It should be borne in mind, however, that the names found on the bullae were popular in ancient times and it is equally possible that there is no connection between the names found on the bullae and the person mentioned in the Bible.”[7]

During the early history of the field, methodological caution such as this was not the norm. However, it soon became evident that there had been some misidentifications. For example, W. F. Albright had argued that the stamped jar handles he found at Tell Beit Mirsim inscribed “Belonging to Eliakim, the steward of Yokan” were to be associated with King Jehoiachin.[8] After all, the title “steward” was one that could be associated with the throne, and “Yokan” was arguably a variant of the throne name Jehoiachin. Ultimately, however, it became apparent that the Eliakim jar handles were to be associated with the late-eighth century or the very early-seventh century; therefore, it was not tenable to argue that these were to be associated with Jehoiachin (r. 598/7 B.C.E.). Albright’s identification seemed rational, but it was wrong.

Sometimes ancient inscriptions will contain a personal name and complementary data. Data such as this would have been useful in antiquity for a number of reasons. For example, use of a title could convey the vocation (and status) of a person. Thus, a seal from Mispah refers to “Ya’azanyahu servant of the king.”[9] A bulla from the City of David contains reference to “[Tobshillem] son of Zakar, the physician.”[10] From the Aramaic Persepolis corpus, there are references to the vocation of treasurer. For example, Text 1 refers to “Data-Mithra the treasurer.”[11] Within the corpus of Ammonite inscriptions, a magnificent seal refers to “Palatiy ben ma’ash, the recorder.”[12]

Sometimes within the epigraphic corpus, there will be a personal name, a patronymic, and a title. Thus, a beautiful ossuary from Mount Scopus is inscribed with the words “Yehosep, son of Hananya, the scribe.”[13] This sort of data can be very useful for a modern scholar attempting to do prosopography.

Although quite rare, there are occasions when someone attested in the epigraphic record can be identified, with enormous (or even complete) certitude, with someone known from literature. Normally, this requires substantial and detailed corroborating evidence. For example, the Moabite Stone contains reference to Mesha King of Moab. Within it, there is reference to the Moabite site of Dhibon and also to the fact that Moab was under the hegemony of Israel during the reign of Omri of Israel. Then, Mesha states that he was able to secure Moab‘s independence during the reign of Omri’s “son.”[14] Because of the correspondences of the personal names, the title king of Moab, and the general chronological harmony, it is convincing to argue that the Mesha of the Moabite Stone is the Mesha named in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., 2 Kgs 3:4-5). Ultimately, it is the convergence of precise, rather unequivocal, data that is required for assumptions about such identifications.

Significantly, during the latter part of his career, Nahman Avigad began to argue for more rigorous methodologies for attempts to affirm that a personal name attested in the epigraphic corpus refers to a figure attested in the Hebrew Bible (during the earlier part of his career, he had made some misidentifications). To be precise, he states that the name and the patronymic must be the same in the epigraphic corpus and the Hebrew Bible. Furthermore, he affirms that both must hail from the same chronological horizon (i.e., the archaeological context for the inscription and the putative historical context for the biblical personage must be the same). Finally, he affirms that the presence of a distinctive title in the epigraphic and biblical corpus fortifies the identification. Nevertheless, Avigad was not satisfied even with this, for he also stated that because of the preponderance of certain names, the presence of the same personal name and patronymic cannot be understood as demonstrative of the certainty of an identification.[15]

II. The Talpiyot Tomb

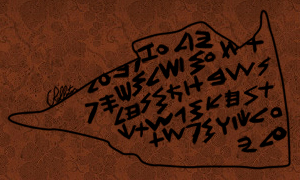

Yosef Gat conducted a salvage excavation at a tomb in the Jerusalem neighborhood of East Talpiyot in 1980. The tomb has been described in some detail.[16] Within the tomb complex, ten ossuaries were found. Six of the ossuaries were inscribed.[17] Four of the ossuaries were not inscribed. One of the four ossuaries, plain and without an inscription, was quite damaged.[18] Based on the totality of finds in the tomb, Amos Kloner states that the tomb can be dated “from the end of the first century B.C.E. or the beginning of the first century C.E., until approximately 70 C.E.” Furthermore, he states that it can be estimated that the bones of a total of thirty-five people were recovered from the tomb: seventeen people were found in the ossuaries, and the bones of a total of eighteen people were found outside the ossuaries.[19] The inscriptions are as follows: (1) Mariamenou {e} Mara (Mariamne).[20] (2) Yhwdh br Yshw’ (Yehudah bar Yeshua’). (3) Mtyh (Mattiyah). This can be considered a variant of the name Mttyhw (Matthew). Note also the inscription Mt{y}h that is on the interior of the ossuary. (4) Yshw’ br Yhwsp (Yeshua bar Yosep).[21] (5) Ywsh (Yoseh). (6) Mryh (Maryah).For the purposes of prosopography, it is mandatory to note that the personal names Yosep, Yeshua’, Yehudah, Mattiyah, Maryah, and Miriamne all have multiple attestations in the multilingual corpus of ossuaries.[22] Moreover, for most of these names, Tal Ilan has noted that they are very common.[23] Furthermore, it should also be emphasized that we have a partial dataset. That is, sample size is always an issue for the field of epigraphy, and the ossuary inscriptions are no exception.

Nevertheless, some scholars have argued that the ossuaries and remains of the Talpiyot tomb can be identified with Jesus of Nazareth and his family. To be precise, it has been argued that the ossuary of Yeshua’ bar Yosep is that of Jesus of Nazareth, the ossuary inscribed Maryah is that of the mother of Jesus of Nazareth, the ossuary inscribed Mariamne is that of the Mary Magdalene of the Gospels, the ossuary inscribed Yoseh is that of Jesus’ brother Joseph, that of Yehudah bar Yeshua’ is that of a son born to Jesus and Mary Magdalene, and the ossuary inscribed Mattiyah is also that of a relative of Jesus of Nazareth. It is also affirmed that the persons buried in the ossuary inscribed Yeshua’ bar Yosep and that inscribed Mariamne {e) Mara were married. Finally, it is even argued that the ossuary with the inscription Ya’akov bar Yosep ‘ahui d Yeshua’ (i.e., the “James Ossuary”) was stolen from the Talpiyot tomb decades ago (and those who argue this implicitly assume that the entire inscription is ancient). It should be emphasized, however, that the origin and chain of custody for the Ya’akov Ossuary are not known and that it is not possible to reconstruct it with any certitude (nor is it even possible to establish the authenticity of the entire inscription). Therefore, any attempt to use it as corroborating evidence is most precarious indeed.[24]

Note, however, that for these six inscribed ossuaries from the Talpiyot Tomb, there are just two personal names with patronymics: (1) Yehuda bar Yeshua’ and (2) Yeshua’ bar Yosep. This is a pivotal issue because without patronymics it is not possible for someone in the modern period to ascertain the precise kinship relationships of antiquity. To be sure, such tombs were “family tombs,” but to assume that such a tomb represents some sort of nuclear family and to assume that one can discern the nature of the relationships within that family without empirical evidence is problematic. For example, the assumption of these scholars is that the Yoseh of the Yoseh Ossuary was the son of Yosep. However, there is no patronymic on this inscription and so to assume that Yoseh was the son of Yosep (and thus the brother of Jesus) is problematic. That is, Yoseh could be the son of Mattiyah, or the son of Yehudah, or the son of Yeshua’. Perhaps, he was the father of Maryah, or the father of Miriamne, or Mattiyah. Maybe he is the uncle of one of these. Perhaps, Yoseh was the son or father or brother or uncle of someone who was buried in one of the ossuaries that does not contain an inscription. It is possible to suggest that he was a cousin of someone in the tomb. Not all of these are mutually exclusive, but ultimately, because there is neither patronymic, statement of relationship (e.g., brother), or title, any suggestion about the relationship of Yoseh to those interred here remains conjecture and speculation.

Similarly, for Maryah, the assumption of those propounding that this is the family tomb of Jesus of Nazareth is that this woman is the mother of Yeshua’ bar Yosep. However, it is tenable to suggest that she was the wife of Yehudah, or the wife of Yoseh, or the wife of Mattiyah, or the wife of Yeshua’. She might have been the benevolent and kind aunt of someone buried in the tomb. She might have been the cousin of someone buried in the tomb. Sometimes we have complementary data. For example, an ossuary from the Kidron Valley is inscribed with the words: “Shalom, wife of Yehudah.”[25] However, for Maryah we simply do not have such data; thus, to assume that a modern scholar can discern and make an affirmation about the nature of some relationship is risible.

Of course, it has also been suggested that the Mariamne ossuary inscription is to be identified with the Mary Magdalene of the Gospels. The problem is that Mariamne is hardly a unique name; moreover, the ossuary inscription does not contain the word “Magdalene.” Sometimes, we do have data about the region from which the deceased hailed. For example, an ossuary from the Kidron Valley contains a Greek inscription with the words, “Sara (daughter of) Simon of Ptolemais.”[26] However, the Mariamne ossuary does not contain such a reference (i.e., no “Magdala”). Therefore, for someone to assume that the Mariamne of the ossuary must be the Mary Magdalene of the Gospels is without justification. Again, she could be the wife of Mattiyah, Yoseh, Yehudah, or Yeshua’. She could be the sister of any person in the tomb. She could also be the aunt of any person in the tomb.[27] In fact, she could even be the sister of Yeshua’ (the DNA just ruled out their having the same mother, but it did not rule out their having the same father but different mothers). Again, not all of these are mutually exclusive, but the point is that to assume that one can state the nature of the relationship of the Mariamne of the ossuary to the Yeshua’ Ossuary is not acceptable.

Of course, there has been some appeal to both statistics and patinas. This too is problematic. Regarding the statistics, Andrey Feuerverger has posted an open letter describing his basic premises and assumptions. For example, “we assume that ‘Mariamenou e Mara’ is a singularly highly appropriate appellation for Mary Magdalene.” He then continues and states, “Note that this assumption is contentious and furthermore that this assumption drives the outcome of the computations substantially.” Moreover, Feuerverger also states that “We assume that Yose/Yosa is a highly appropriate appellation for the brother of Jesus who is referred to as Joses in Mark 6:3 of the NT.” He then continues that “It is assumed that Yose/Yosa is not the same person as the father Yosef who is referred to on the ossuary of Yeshua.”

I am confident that statisticians will be critiquing Feuerverger’s data in some detail, but I would simply note that “assuming” things such as the fact that “Mariamenne e Mara” is a highly appropriate appellation for Mary Magdalene is problematic. Similarly, to assume that “Yoseh” is a highly appropriate appellation for the brother of Jesus would also seem to be a problem. That is, I would concur that this could be an acceptable manner for an ossuary inscription to refer to him, but to suggest that it is “highly appropriate” and then factor that into the assessment is most presumptive and methodologically problematic.

Actually, the fact of the matter is that the Yosep of the patronymic and the Yoseh of the ossuary could be the same person. After all, these ossuaries were inscribed at two different times and in neither case is there a patronymic for “Yosep” or “Yoseh.” “Yosep” is the more formal form, and “Yosi” is less formal (and more endearing). Without a patronymic, it is simply not sage to make any assumptions. Note that even Feuerverger concedes that his assumption about the identification of the Mariamne of the ossuary and Mary Magdalene “drives the outcome of the computations substantially.” This is a telling concession. Moreover, with regard to the DNA evidence, it simply cannot carry the freight that has been placed on it. That is, Jacobovici and Pellegrino assume that just because the mitochondrial DNA do not “match,” that Yeshua’ and Mariamne were married. Perhaps, however, they were brother-in-law and sister-in-law, perhaps they were paternal aunt and nephew, perhaps they were paternal cousins, perhaps they were father-in-law and daughter-in-law. Numerous options present themselves. Jacobovici and Pellegrino state that the DNA do not “negate [their] conclusion,” but this is much different from proving their conclusion. Furthermore, with regard to the analyses of the patinas on the Talpiyot ossuaries and those of the “Ya’akov Ossuary,” two things are readily apparent: (a) ossuaries made from the same basic Jerusalem limestone and stored in rock hewn tombs of the same city can have similar patinas, and (b) the control group must be much larger for decisive statements to be made about the differences between the patinas on ossuaries in Jerusalem tombs of the same chronological horizon (e.g., the Talpiyot tomb and the Ya’akov Ossuary).[28] That is, the laboratory tests performed are not sufficient to permit the positing of a complete nexus of relationships in the face of a dearth of the necessary prosopographic data, nor are they sufficient for suggesting that the Ya’akov Ossuary hailed from the Talpiyot tomb.

Thomas Lambdin’s famous dictum is that within the field we often “work with no data.” This is a hyperbole, but the fact remains that we do work with partial data, and sometimes the data we have are just plain opaque. With the Talpiyot tomb, there is a dearth of prosopographic data, and this is a fact. Based on the prosopographic evidence, it is simply not possible to make assumptions about the relationships of those buried therein, and it is certainly not tenable to suggest that the data are sufficient to posit that this is the family tomb of Jesus of Nazareth. Finally, it should be stated that at this juncture there is nothing in the statistical or laboratory data that can sufficiently clarify the situation, and I doubt that there ever will be.[29]

Christopher A. Rollston, Emmanuel School of Religion, A Graduate Seminary

Notes

[1] Among the seminal studies are those of Lawrence Stone, “Prosopography,” Daedalus 100 (1971): 46-79; Thomas F. Carney, “Prosopography: Payoffs and Pitfalls,” Phoenix 27 (1973): 156-79. Because of the massive amounts of epigraphic material in Mesopotamian cuneiform, there has been substantial work in the field of prosopography. For example, see Karen Radner, ed., The Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian Empire: Volume 1, Part 1: A (Helsinki: Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, 1998); idem, The Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian Empire: Voume 1, Part 2: B-G (Helsinki: Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, 1999). See also the many fine contributions of R. Zadok, such as The Pre-Hellenistic Israelite Anthroponymy and Prosopography, OLA 28 (Leuven: Peeters, 1989). [2] Douglas M. Gropp, Wadi Daliyeh II: The Samaria Papyri from Wadi Daliyeh, DJD 28 (Oxford: Clarendon, 2001), 35 (no. 1).Masada I: The Aramaic and Hebrew Ostraca and Jar Inscriptions (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1989), 40.Israel (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 1994), 258 (no. 868).Israel Museum, and Anson Rainey and Zeev Herzog of Tel Aviv University for allowing me to collate these materials.David,” in Eretz Israel 18 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1985), 73-87 [Hebrew]; idem, “A Group of Hebrew Bullae from the City of David,” IEJ 36 (1986): 16-18.David Excavations: Final Report VI, Qedem 41 (Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2000), 33. I am grateful to the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Israel Museum for allowing me to collate this corpus of bullae.Judah, with some Observations on Ezekiel,” JBL 51 (1932): 77-106.Persepolis, University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications 91 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 71-74 (no. 1).Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society1987), 235-37 [Hebrew], English summary 79. Recently, Lawrence J. Mykytiuk has produced a thorough volume on the subject of prosopography of Iron Age Northwest Semitic inscriptions. Namely, see his Identifying Biblical Persons in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions of 1200-539 B.C.E.. SBLAB 12 (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2004).East Talpiyot, Jerusalem,” ‘Atiqot 29 (1996): 15-22.New York: Harper Collins, 2007), passim. For the DNA evidence, see especially 167-174; James D. Tabor, The Jesus Dynasty: The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family and the Birth of Christianity (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006), especially 4, 25, 56, et passim. Although Tabor’s volume is more erudite and also nuances certain positions differently, it still suffers from the same sorts of erroneous methodologies and assumptions that are part of the volume by Jacobovici and Pellegrino.DNA evidence with me.

[3] Yigael Yadin and Joseph Naveh,

[4] L. Y. Rahmani, A Catalogue of Jewish Ossuaries in the Collections of the State of

[5] For the epigraphic materials from Arad, see Yohanan Aharoni, Arad Inscriptions (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1981), numbers 1-18, 24 (ostraca), 105-107 (seals). I am grateful to Director Hava Katz of the Israel Antiquities Authority, Chief Iron Age Curator Michal Dayagi Mendels of the

[6] Yigal Shiloh, “A Group of Hebrew Bullae from the City of

[7] Yair Shoham, “Hebrew Bullae,” in City of

[8] William F. Albright, “The Seal of Eliakim and the Latest Pre-Exilic History of

[9] W.F. Badè, “The Seal of Jaazaniah,” ZAW 51 (1933): 150-56.

[10] Yair Shoham, “Hebrew Bullae,” 35 (no 6).

[11] Raymond A. Bowman, Aramaic Ritual Texts from

[12] M. Abu Taleb, “The Seal of plty bn m’sh the mazkir,” ZDPV 101 (1985): 21-29. Note that some consider this seal to be Moabite. For the purposes of this paper, this is not a relevant point. I am grateful to the Department of Antiquities of Jordan and Director Fawwaz al-Khrayshah for permission to collate this seal.

[13] Rahmani, A Catalogue, 262 (no. 893).

[14] For the text of the Mesha Inscription, see especially Andrew Dearman (ed), Studies in the Mesha Inscription and Moab (Atlanta: Scholars, 1989).

[15] Nahman Avigad, “On the Identification of Persons Mentioned in Hebrew Epigraphic Sources,” in Eretz-Israel 19 (

[16] Amos Kloner, “A Tomb with Inscribed Ossuaries in

[17] Rahmani, A Catalogue, 222-224 (nos. 701-709).

[18] Rahmani, A Catalogue, 222 (comment 1). This plain, broken ossuary does not appear to have been retained, but note that it was plain, not inscribed.

[19] Kloner, “Tomb,” 21, 22.

[20] Note that this inscription is Greek; it is the sole Greek inscription discovered in this tomb. Rahmani suggests that there is a stroke between the two names that should be considered an êta. Based on similar constructions in the corpus, Rahmani also states that he believes the name Mara is a short form of the name Martha and that this is the case of a double name (Rahmani 1994, no. 701). Contra some, I am not at all convinced, on the basis of the epigraphic or literary evidence, that Mara should be understood as “Master” and then posited to be some sort of decisive reference to Mary Magdalene. In fact, I find such arguments to be weak and anachronistic.

[21] Note that Rahmani (1994, no 704) states that the first name is “difficult to read.” However, he believes that his reading of the personal-name Yeshua’ is corroborated by the inscription Yehudah bar Yeshua’.

[22] See the index in Rahmani, Catalogue, 292-297. Also, note especially that Yoseh is attested multiple times (Rahmani, Catalogue, 295), so any suggestion that this is a unique nickname in the gospels (Mark 6:3) is erroneous. [23] See especially, Tal Ilan, Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity (Mohr Siebeck, 2002), passim. Note that the variant spellings of Mariamne (Rahmani, The Catalogue, 296) are not an orthographic problem from the perspective of epigraphy.

[24] For the espousal of these views, see Simcha Jacobovici and Charles Pellegrino, The Jesus Family Tomb: The Discovery, the Investigation, and the Evidence that Could Change History (

[25] Rahmani, A Catalogue, 81 (no. 24).

[26] Rahmani, A Catalogue, 102 (no. 99).

[27] Note that she could even be the aunt of Yeshua’, on his father’s side.

[28] For a general discussion of some of the problems that have been part of laboratory tests of epigraphic objects, (including the Ya’akov [James] Ossuary) see Christopher A. Rollston, “Non-Provenanced Epigraphs I: Pillaged Antiquities, Northwest Semitic Forgeries, and Protocols for Laboratory Tests,” Maarav 10 (2003): 182-91.

[29] That is, because of the numbers of burials in the tombs, the practice of interring the skeletal remains of multiple people in a single ossuary, and the possibility of contamination of laboratory data, the notion that decisive data can be produced seems to me to be most difficult. My thanks to Lindsay Hunter and Ryan Jackson for discussion of the

Comments on this article? email: forum@sbl-site.org

Let us know if you would like your comments sent to the author or considered for publication as a letter to the editor. Please include your full name and, if you would like, your affiliation.

Citation: Christopher A. Rollston, ” Prosopography and the Talpiyot Yeshua Family Tomb: Pensées of a Palaeographer,” SBL Forum , n.p. [cited March 2007]. Online:http://sbl-site.org/Article.aspx?ArticleID=649

No Comments to “The Jesus Family Tomb”