Introduction:

Tel Aviv University’s Epigraphic Hebrew Project is among the most innovative and important in the world, with the collaboration of scholars from the hard sciences, epigraphy, and archaeology. During recent years, a number of seminal articles have been published as part of this project. Very recently, an additional multiple-author article has appeared in PNAS (April 2016). This article is entitled “Algorithmic handwriting analysis of Judah’s military correspondence sheds light on composition of biblical texts.” I have served as a consultant on Tel Aviv’s Epigraphic Project and find the project to be particularly important, productive, and auspicious. I am not among the authors of this article, but I find the technology, hard sciences, and mathematics in the article to be especially impressive. At this juncture, I shall summarize the salient components of the PNAS article, some of the conclusions of the article, and then I shall offer some sober reflections.

__

I. The Tel Aviv University Study, the Postulates, the Conclusions:

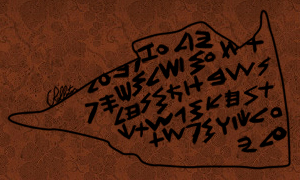

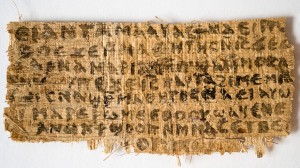

The Tel Aviv study is based on an innovative an important algorithmic analysis of sixteen ostraca (i.e., ink inscriptions on broken piece of pottery called potsherds) from the Judean fortress of Arad. The English publication of the Hebrew-language Inscriptions from Arad appeared in print in 1981 (Aramaic inscriptions were also found there, but from a later period). The volume is entitled Arad Inscriptions, authored by Yohanan Aharoni (Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society). The Hebrew inscriptions in this volume number 112 (this includes ostraca, inscriptions incised into pottery, and seals).

(1) The Tel Aviv University study published in PNAS analyzed the following ostraca: 1,2,3, 5, 7, 8, 16, 17, 18, 21, 24, 31, 38, 39, 40, and 111. (2) The Tel Aviv study presupposes that all sixteen of these inscriptions were written ca. 600 BCE (pages 2-3). (3) Based on the analysis of the handwriting on these sixteen inscriptions, the authors stated that they “deduce the presence of at least six authors” in this group of sixteen ostraca (page 1). (4) The authors of the PNAS study believe that some of these ostraca were “most likely” composed at Arad (e.g., Ostraca 31 and 39) and some were probably dispatched from other locations (e.g., Ostraca 7, 18, 24, 40). Within the abstract it is stated even more emphatically. Namely, “our algorithmic analysis, complemented by the textual information, reveals a minimum of six authors within the examined inscriptions. The results indicate that in this remote fort literacy had spread throughout the military hierarchy, down to the quartermaster and probably even below that rank” (page 1). (5) Because Arad was a military fortress and there are some named military officials, the authors posit that there must have been “a proliferation of literacy” at this time period (NB: the term “proliferation of literacy” occurs numerous times in the article), that is, around 600 BCE. (6) Part of their reasoning is based on the fact that there were similar fortress sites at places such as Tel Malhata, Lachish, Horvat ‘Uza and so from this they contend that by “extrapolating the minimum of six authors in 16 Arad ostraca to the entire Arad corpus, to the whole military system in the southern Judahite frontier, to military posts in other sectors of the kingdom, to central administration towns such as Lachish, and to the capital, Jerusalem, a significant number of literate individuals can be assumed to have lived in Judah ca. 600 BCE” (page 3-4). (7) The authors then argue that “the spread of literacy in late-monarchic Judah provides a possible stage setting for the compilation of literary works. “ The authors concede that “biblical texts could have been written by a few and kept in seclusion in the Jerusalem Temple, and the illiterate populace could have been informed about them in public readings and verbal messages by these few.” But they contend that “widespread literacy offers a better background for the composition of ambitious works such as the Book of Deuteronomy, and the history of Ancient Israel in the Books of Joshua to Kings” (page 4). (8) Ultimately, the authors conclude that by ca. 600 BCE, therefore, all of this “implies that an educational infrastructure that could support the composition of literary texts in Judah already existed before the destruction of the First Temple” (586 BCE).

___

II. Rollston’s Reflections

A. There has been sufficient inscriptional evidence for some time from the world of ancient Israel to contend that already by 800 BCE there was sufficient intellectual infrastructure, that is, well-trained scribes, able to produce sophisticated historical and literary texts. Indeed, I argued for this a decade ago in a detailed epigraphic article (Rollston 2006), and I was not the first epigrapher to do so. Moreover, among the most important recent monographs discussing scribal education in ancient Israel, within the broader context of the ancient Near East are those of David Carr (2005), Karel Van der Toorn (2007), Seth L. Sanders (2009). And long before this, the subject of schools and literacy in ancient Israel was the object of much discussion in scholarly literature, with Hermisson (1968), Whybray (1974), Lemaire (1981) being among the most enduring. Reference could also be made to the work of D.W. Jamieson-Drake’s work (1991), although a number of scholars have discussed the serious problems with the data and the assumptions that served as a foundation for that volume. And, of course, I would wish to emphasize the careful and enduring work of the great James Crenshaw on the subject of scribal education in ancient Israel (1985; 1998). In short, the subject of writing and literacy in ancient Israel and Judah has a long history within the field. As for my own work, the main point for which I have contended is that we have sufficient epigraphic evidence to demonstrate that there was detailed, sophisticated, standardized education in the Old Hebrew writing system (script, orthography, hieratic numerals, phonology) in ancient Israel and Judah. And the evidence for that is already present by ca. 800 BCE (Rollston 2006; 2008; 2010; 2012). For this sophisticated scribal apparatus, I used the term “intellectual infrastructure” during a presentation in Jerusalem during May of 2013 (now forthcoming 2016). I believe that the cumulative epigraphic evidence from sites such as Kuntillet Ajrud, Beth Shean, Tel Rehov, Arad, Samaria, Jerusalem, Lachish, Horvat Uza, Tel Ira, and Beer-Sheva is compelling. And epigraphs in Phoenician, Moabite, Aramaic, Ammonite, and even Edomite augment the Old Hebrew data substantially. More recently, I have discussed scribal curriculum in Old Hebrew in some detail (2015; forthcoming 2016). Thus, the first point that I would wish to make regarding the PNAS study is that with its date of ca. 600 BCE, this study is too conservative. I would contend that we have such evidence already two hundred years prior to this. As an ancillary note, I should like to emphasize that I am not arguing here arguing that this or that portion of the Bible hails from a particular place and time (that is a separate, longer discussion, of course, because of the long transmission history of much of the biblical material), although I concur with the consensus of the field that the late 7th and early 6th centuries were periods of substantial literary productivity in Judah. But most importantly, to reiterate, I am contending that the epigraphic evidence at hand demonstrates rather nicely that there were educated scribes in Israel and Judah by the late 9th and early 8th centuries BCE and that these scribes were capable of writing fine historical and literary texts. Thus, in sum, as for the PNAS article, I would say (with some good-natured humor and a turn of phrase), “I see your 600 and raise you 200” (i.e., to ca. 800 BCE).

B. The authors of this study contend that all sixteen of the ostraca they analyzed were written around 600 BCE. However, the original excavator (Yohanan Aharoni) argued that some of these ostraca (i.e., the ones studied in the PNAS article) came from stratum VI (e.g., 1-24, etc.), some from stratum VII (e.g., Arad 31, 38, 39), and at least one (Arad 40) from stratum VIII (Aharoni 1981). In other words, the original excavator argued that the sixteen ostraca used in this study were from three different chronological horizons, not one. That is, the original excavator believed that these ostraca definitely did not come from the same time-frame, but rather during the course of ca. a century. There has been a substantial amount of discussion regarding the stratigraphy of Arad (especially Z. Herzog 2002, 3-109) and even Aharoni noted that some of the inscriptions were found in loci that he viewed as mixed or unclear (see Aharoni 1981, 181-185 for a loci-table and also his discussion in the body of the volume for all the ostraca). I conversed with Professor Ze’ev Herzog about Arad about the stratigraphy of Arad VI and VII a number of years ago (namely, 1998), as I wished to see strata VI and VII as contemporary. At that time, he emphasized to me that these were separate strata, sequential, not contemporary. That is not to suggest that there is a vast expanse of time between these two strata, as there is not, but the point he emphasized was that stratum VII and VI were sequential, not contemporaneous. In terms of absolute dates, Aharoni dated the Stratum-VII destruction to ca. 609 BCE and the Stratum-VI destruction to ca. 586 BCE. As for stratum VIII, the dates for it have been much discussed as well. Aharoni argued that Stratum VIII-destruction was ca. 701 BCE (during the punitive campaign of Sennacherib against Judah). Some would wish to push the date a little later, of course. In any case, Arad Ostracon 40 is one that Aharoni considered to hail from Stratum VIII. Nadav Na’aman (one of the authors of the PNAS study) has argued that Arad Ostracon 40 is to be associated with the ostraca from Arad VI. His reasons are as follows: (a) “No eighth century letter written on a potsherd has been discovered in any site in Palestine….it seems that writing letters on pottery began only in the seventh century BCE.” (b) “the orthography indicates a relatively late date, with internal matres lectionis for ‘yš (lines 7-8) and yhwd[h] (line 13).” (c) “Epigraphically, the letter [Arad 40] has many parallels with both Stratum VIII and VII-VI ostraca…” (d) “The situation described in the ostracon closely matches the reality of the late years of the Judahite monarchy.” (e) In addition, Na’aman suggests that “Malkiyahu, the recipient of the letter [Arad Ostracon 40] is possibly the same officer Malkiyahu the son of Zerabu’ur, who led troops to Ramat-Negev according to Ostracon 24 from Arad” (Na’aman 2003, 199-204). The authors of the PNAS article embrace Na’aman’s view (see footnote on page 3, and note also that the authors of the PNAS study are also very much aware of the difficult stratagraphic history of Arad and the secondary literature discussing it). I would suggest that a fair amount of Na’aman’s reasoning is potentially problematic. (a) Thus, regarding epistolary texts in the ancient Near East, I would emphasize that this is a very old practice, centuries older than even the oldest Levantine alphabetic texts. That is, letters were around in the ancient Near East for a very long time. Moreover, using potsherds as a medium for writing alphabetic texts is also well attested long before ca. 600 BCE, of course. I would be cautious, therefore, about arguing on the basis of an absence of an epistolary ostracon, that we should date Arad 40 to the early 6th century (i.e., Stratum VI). (b) The usage of internal matres lectionis in Old Hebrew inscriptions does increase during the late 7th and early 6th centuries, but the fact of the matter is that we do have the usage of matres lectionis in Old Hebrew inscriptions already by the end of the 8th century, with the Royal Steward Inscription from Jerusalem being a prime example (Rollston 2006, 63-64). (c) As for the script, I find some of the forms in Arad 40 to reflect a time-frame prior to the late 7th or early 6th century. In short, I do not see a compelling palaeographic reason for dropping the date of Arad 40. (d) Judah was in a difficult political situation from the reign of Ahaz (d. ca. 715 BCE) to the assassination of the Judean Governor Gedaliah (sometime shortly after the fall of Judah in 586 BCE). And Edom was a alive and well in the region for much of this period, as the two-volume magnum opus edited by Thomas E. Levy, Mohammad Najjar, and Erez Ben-Yosef demonstrates (2014). Therefore, I find it difficult to assume that the only time during the final century of the First Temple Period that Edom could have been a nemesis for Judah was ca. 600 BCE. (e) As for the personal name Malkiyahu, note that Na’aman used the word “possibly.” That’s important. Moreover, a quick look at the Hebrew Bible reveals that some eight people have names based on this root, and I’m confident that there are more (if I looked harder). In short, this is not a rare name. So to assume that they are the same person is…well…an assumption that might be erroneous. Note in this connection Lawrence Mykytiuk’s foundational work on personal names, a work that reminds us all of the importance of having at least a shared name and a shared patronymic (or some other inscribed feature, such as the same title, etc., etc.) for any attempt to suggest some sort of identification between two individuals (2004). And, of course, in Arad Ostracon 24, we have reference to someone called Malkiyahu son of Zerab’ur, but in Arad Ostracon 40 we have reference simply to Malkiyahu (with no patronymic). That’s a problem for anyone attempting to posit a certain, or near-certain identification. Note, therefore, that because papponymy (naming after a grandfather) was a very common practice in the ancient Near East (including Israel and Judah), one could make a decent case that the Malkiyahu of Arad Ostracon 40 is the grandfather of the Malkiyahu of Arad Ostracon 24, with the former being a well-known patriarch of the family. Although this might (and I repeat, *might*) account for most of the data that we have (including the fact that in the case of Arad 40 we do not have a patronymic but in Arad 24 we do), I am disinclined to speculate. After all, without a patronymic, and with names based on the root mlk being fairly common, it is simply too problematic to argue that these two are definitely the same person. So, I won’t. In this too, therefore, I must differ with the authors of the PNAS study.

C. As for the contention of this Tel Aviv Study that we can posit a “proliferation of literacy” at ca. 600 BCE, based on the assumption that there are at least six different hands in the sixteen ostraca that were analyzed, I would simply suggest that this is a very broad assumption that I would not be inclined to make. After all, the assumption of the PNAS study that all of these ostraca come from ca. 600 BCE is difficult to embrace (see discussion above). Furthermore, in reality we do not know how many of these ostraca might, or might not, have been produced at the site of Arad. Compare, however, some of the assumptions of the Tel Aviv study (e.g., page 3, and footnote). That is, from my perspective, there is nothing in the content of these ostraca that make it at all compelling to state that any were definitely produced at Arad. After all, even lists could have come from elsewhere. That is not to say that there were not readers and writers at Arad. There were. After all, that’s where the ostraca ended up. But the origin-point is not something that can be ascertained on the basis of the data at hand. Thus, rather than arguing on the basis of sixteen ostraca (that ended up at Arad) that we have a “proliferation of literacy,” I would simply conclude that we have some readers and writers of inscriptions at Arad. That’s all we can say. Who were these readers and writers at Arad? I would emphasize that these writers may very well have been scribes associated with the army. After all, we do have references in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., 2 Kings 25:19; Jeremiah 52:25) to the “scribe of the leader of the army” (and I find this title to be something that can be considered a credible, historical thing). In addition, I do think that it is reasonable to contend that some military officials (at various levels of the command structure) could read and write, and I have noted this in print as well. But, I would wish to emphasize that we do not have evidence for enlisted soldiers, that is, the average soldier, reading and writing. We have evidence for some literacy among some of the army officials. That’s what I think we can say. Furthermore, although this study does not suggest this, per se, some have already seized upon it (within hours of the appearance of this study!) and begun to contend that we have people from all walks of life writing and reading in First Temple Judah. That’s quite a leap. I would, therefore, emphasize that we have no evidence for the common folk writing and reading, not from the epigraphic record and not from the Bible (see especially Ian Young’s articles on literacy, 1998a; 1998b). I’d like to be able to state that there were carpenters who built houses by day and read papyri manuscripts at night. And I’d like to say that there were blacksmith’s shaping metal over a furnace during the day and penning contracts at night. And I’d like to be able to say that there were potters turning pots on the wheel by day and writing alphabetic acrostics by the light of olive-oil lamps before dawn. And I’d like to say that there were shepherds guarding their flocks by day and writing out parchment king-lists by night. But I can’t. We have no inscriptions with content that causes us to think that people from these vocations are producing or consuming texts (on some poorly written texts, by people with little training, see below). Some might counter that we seem to have so many more inscriptions from the late First Temple Period and so we must assume the proliferation of literacy. I would counter that we also have a growing population and thus a burgeoning governmental apparatus during the late First Temple Period, and so we have a need for more professional scribes and literate elites. Governments need scribes and literate officials. And as government grows, so does the number of scribes. That’s fine, but it does not mean that we can assume that the general populace (people from all walks of life) is reading and writing texts. Furthermore, since we have a growing population in Judah, even though we have more scribes and literate officials, it could be argued that the percentage of the population that is literate stays about the same. Also perhaps of some consequence regarding readers and writers in antiquity, we actually have a Jerusalem scribe in the early 2nd century BCE who notes that scribes were reading, writing, traveling, and solving riddles….but the average person was simply not able to do such things (Sira 38:24-39:11). It is reasonable to posit that this was even more the case during the First Temple Period.

D. To be sure, most people contemplating the subject of literacy today bring their own experiences to the table, namely, the widespread literacy of the modern world. But in the modern world, we normally have government mandated education of (for all practical purposes) the entire population. Things were very different in antiquity. We have no evidence at all of government mandated education of large portions of the populace in antiquity. So what do we have? We know that scribes and high governmental officials (temple, palace) and military officials read and wrote. Did some of the trades-people sometimes learn to write? I suppose so. But was it common? No, I don’t think so. Furthermore, note that we have several hundred Old Hebrew inscriptions from the Iron Age that are very well done, with a sophisticated knowledge of letter morphology, stance, orthographic conventions, the use of hieratic numerals, knowledge of epistolary conventions, some understanding of phonology, the ability to use effectively different tenses, parts of speech, and to do so very well. I’d like to suggest that everyone could do that, but I can’t. And, in fact, when someone without formal, standardized education attempted to write an Old Hebrew inscription (or any other ancient script), it is painfully obvious. And we do have a few inscriptions to prove that! In short, much as it pains me to say it, the writers in readers of texts in ancient Israel and Judah were elites, not the common person. In essence, the common person could get along just fine in life without learning to read or write (see Rollston 2006, 48-49 regarding the time it takes to learn one’s first writing system, even an alphabetic one).

Conclusion:

So, in sum, the Tel Aviv Epigraphic Project is scintillating. The technology and talent that the authors of this PNAS article bring to the table is unmatched anywhere in the world. But the sociological conclusions about the “proliferation of literacy” in Judah is not something that can be posited on the basis of this study. The methodology is stunningly important, but I would wish to see more caution regarding the conclusions.

__

Citations

Aharoni, Y. Arad Inscriptions. Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society, 1981.

Carr, D.M. Writing on the Tablet of theHeart: Origins of Scripture and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Crenshaw, J. L. “Education in Ancient Israel.” JBL 104 (1985): 601-615.

_____. Education in Ancient Israel: Across the Deadening Silence. New York: Doubleday, 1998.

Faigenbaum-Golovin, S.; Shaus, A.; Sober, B. ; Levin, D.; Na’aman, N.; Sass, B.; Turkel, E.; Piasetzky, E.; Finkelstein, I. “Algorithmic handwriting analysis of Judah’s military correspondence sheds light on composition of biblical texts.” PNAS Early Edition (April 11, 2016): 1-6.

Jamieson-Drake, D.W. Scribes and Schools in Monarchic Judah: A Socio-Archaeological Approach. JSOTSup 109. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1991.

Hermisson, H. J. Studien zur israelitischen Spruchweisheit. WMANT 28. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1968.

Herzog, Z. “The Fortress Mount at Tel Arad: An Interim Report.” Tel Aviv 29 (2002): 3-109.

Lemaire, A. Les écoles et la formation de la Bible dans l’ancien Israël. OBO 39. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1981.

Levy, T. E., Najjar, M., Ben-Yosef, E., eds. New Insights into the Iron Age Archaeology of Edom, Southern Jordan: Volumes 1-2. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, UCLA, 2014.

Mykytiuk, L. J. Identifying Biblical Persons in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions of 1200-539 BCE. SBLAB 12. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2004.

Na’aman, N. “Ostracon 40 from Arad Reconsidered.” Pp. 199-204 in Saxa Loquentur: Studien zur Archäologie Palästinas/Israels, Festschrift für Volkmar Fritz zum 65. Geburtstag, eds. C. G. Den Hertog, U. Hübner, S. Münger. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag 2003.

Rollston, C. A. “Scribal Education in Ancient Israel: The Old Hebrew Epigraphic Evidence.” BASOR 344 (2006): 47-74.

_____. “The Phoenician Script of the Tel Zayit Abecedary and Putative Evidence for Israelite Literacy.” Pp. 61-96 in Literate Culture and Tenth-Century Canaan: The Tel Zayit Abecedary in Context, eds. R. E. Tappy and P. K. McCarter, 2008.

_____.Writing and Literacy in the World of Ancient Israel: Epigraphic Evidence from the Iron Age. SBL Archaeology and Biblical Studies, 11. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2010.

_____. “An Old Hebrew Stone Inscription from the City of David: A Trained Hand and a Remedial Hand on the Same Inscription.” Pp. 189-196 in Puzzling Out the Past: Studies in Northwest Semitic Languages and Literatures in Honor of Bruce Zuckerman, eds. M. J. Lundberg, S. Fine, W.T. Pitard. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

_____. “Scribal Curriculum during the First Temple Period: Epigraphic Hebrew and Biblical Evidence.” Pp. 71-101 in Contextualizing Israel’s Sacred Writings: Ancient Literacy, Orality, and Literary Production, ed. Brian B. Schmidt. SBL Ancient Israel and Its Literature, 22. Atlanta: SBL, 2015.

Sanders, S. L. The Invention of Hebrew. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Toorn, K. van der. Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Whybray, R.N. The Intellectual Tradition in the Old Testament. BZAW 135. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1974.

Young, I. “Israelite Literacy: Interpreting the Evidence, Part 1. VT 48 (1998a): 239-253.

_____. “Israelite Literacy: Interpreting the Evidence, Part 2.” VT 48 (1998b): 408-422.

Recent Comments