Review of _Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae_

A Review of Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae: Volume 1, Jerusalem, Part 1: 1-704, edited by Hannah M. Cotton, Leah Di Segni, Werner Eck, Benjamin Isaac, Alla Kushnir-Stein, Haggai Misgav, Jonathan Price, Israel Roll and Ada Yardeni. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010. ISBN: 978-3-11-022219-7. Pp. xxvi + 694. $195.

A Review of Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae: Volume 1, Jerusalem, Part 1: 1-704, edited by Hannah M. Cotton, Leah Di Segni, Werner Eck, Benjamin Isaac, Alla Kushnir-Stein, Haggai Misgav, Jonathan Price, Israel Roll and Ada Yardeni. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010. ISBN: 978-3-11-022219-7. Pp. xxvi + 694. $195.

This is the first volume of the new Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae to appear in print. Scholars working in fields such as Epigraphic Hebrew and Aramaic, Hebrew Bible, Second Temple Judaism, the History of Judaism, Hellenistic Greek, Classical Latin, Greek New Testament and Early Christianity will find this volume to be a vade mecum. Moreover, those working in fields such as Hellenistic and Roman history, Jewish burial practices, Jewish personal names (in Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Latin) and the history of Jerusalem will find this volume to be a particularly fertile source of primary data as well. In addition, those interested in subjects such as linguistic and cultural diversity in antiquity will find this volume to be replete with a superabundance of primary data. Ultimately, I would suggest that no scholar working within such fields can afford to be without this volume, and no library with a collection that touches on these fields can afford to be without this volume. It is a veritable sine qua non. To be sure, this volume is rather expensive, but it is certainly worth the purchase price. Within this review, I shall begin with a summary of the scope of this new Corpus, then discuss the contents of this first volume in broad strokes, and conclude with a synopsis of some of the epigraphic material contained in it.

Scope of the entire Corpus. For some time now, scholars have sensed that there needed to be a new corpus of inscriptions from this period and region. After initial discussions in 1997, it was decided that the new corpus would be “restricted to the Graeco-Roman period (beginning with Alexander and ending with the Arab Conquest of Palestine.” However, rather than restricting itself to Greek and Latin (as works focusing on this period have often done), the new Corpus “was to be a comprehensive multilingual corpus of all inscriptions, both published and (so far as possible) unpublished, encompassing the ‘sovereign languages,’ Greek and Latin, alongside the Semitic languages, namely Hebrew, Phoenician and the various Aramaic dialects: Jewish Aramaic, Samaritan, Nabataean, Northern Syriac and Southern Syriac (known also as Christian Palestinian Aramaic).” Furthermore, it was also agreed that it would be important also to include “the proto-Arabic languages, Thamudic and Safaitic, and finally Armenian and Georgian” as well. It was also decided that “Early Arabic inscriptions are outside the time limits of our Corpus and hence not included.” However, it was noted that these are “being collected and edited by Moshe Sharon in the Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae” (pages v-vi). Obviously, therefore, both breadth and depth are envisioned for this new Corpus.

Because this new Corpus has cast its net so widely, it was determined that “the entire Corpus will consist of nine volumes, organized according to major geographical and/or historical divisions in ancient Judaea/Palestina: Jerusalem and its surroundings; the middle coastline north of Tel Aviv and south of Haifa with Caesarea as the focal point; the southern coastline with its urban hinterland; Galilee and the northern coastline including Acco; the Golan Heights; Samaria; Judaea (without Jerusalem) and Idumaea; the Negev.” It should be emphasized, however, that “the order in which the regions are presented here does not reflect the order in which the volumes will appear in print.” Finally, it is also stated that “a final volume will include milestones from the entire territory, including those that no longer bear an inscription, as well as items with unknown or uncertain provenance, in museums and private collections.” Parts of modern Syria and Jordan which were at different times part of the administrative unit which included Iudaea/Palestine (i.e., Batanea, Aurantis, and the Peraea) are not included since nowadays they belong to territories covered by Inscriptions Grecques et Latines de la Syrie or de la Jordanie, respectively” (p. vi).

Naturally, because of the large number of inscriptions that are included in this Corpus, the editors state that “it was not our intention to provide an exhaustive commentary for every single inscription” (p. vii). Similarly, as for the bibliography, it is stated that it “does not claim to be complete; whereas the editors consulted every item in which each inscription was discussed, only the relevant literature has been cited here. Any other procedure would have resulted in an endless list of items, which would be of little interest” (p. vii). Again, this too is entirely understandable and defensible, in light of the large numbers of texts that are part of this Corpus. However, it should also be emphasized that the bibliographies in this volume are really quite thorough. To be sure, they are not exhaustive, but those using the bibliographies will not be disappointed.

Regarding this first volume (parts 1 and 2) it is stated that “the following order has been adopted. First, the inscriptions were divided so far as possible into three chronological groups: (1) The Hellenistic period up to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70; (2) The Roman period from 70 to the reign of Constantine; (3) Late Antiquity, from Constantine to the Arab Conquest.” (p. vii). It is noted that there have been some exclusions, but entirely understandable ones. Namely, the editors state that “on the whole we have not included mass-produced inscriptions such as impressions of amphora-handle stamps, brick-stamps, potter-stamps, stamps on lamps, and pilgrims’ ampullae” (p. vii). Those using this volume might have wished for indices. The editors sensed the importance of this and state that “we regret the absence of a general index in this volume.” However, they do state that “a general index for all the volumes is planned. And we intend to provide a provisional general index to this volume on the Internet” (p. viii). It should also be mentioned that the preface mentions that “an index of names is provided here [in this volume].” There is no index of names in Volume 1, Jerusalem, Part 1: 1-704, but my strong assumption is that this index will be included in the forthcoming Volume 1, Jerusalem, Part 2.

In any case, Volume 1, Jerusalem, Part 1: 1-704 begins with a fairly detailed synopsis of ancient literary references to the city of Jerusalem (pp. 1-37). Moreover, there is a fine summary of the caves and tombs in the region of Jerusalem. In terms of the history of Jerusalem, there are particularly good summaries of the period between the First and Second Jewish Revolts and also of the period from the time of Hadrian to Constantine, and from Constantine to the Muslim Conquest. This section of the volume is reflective of the volume as a whole, namely, detailed reference to relevant ancient sources, replete with citation of the most salient and authoritative modern studies. The remainder of this volume (i.e., Volume 1, Part 1) focuses on “Inscriptions from the Hellenistic period up to the Destruction of the Second Temple.” This material is divided up into four parts: Section A “Inscriptions of religious and public character,” (inscription numbers 1-17, pages 39-64). Section B “Funerary Inscriptions” (inscription numbers 18-608, pages 65-609). Note that the material in Section B is divided according to region or site (e.g., Ramat Eshkol, Kidron Valley [North], Diskin Street, Jason’s Tomb, French Hill, Ramat Rahel, and then a division called “Unprovenanced.” Section C “Instrumentum Domesticum” (inscription numbers 609-692, pages 611-680). Section D: “Varia” (inscription numbers 693-704, pages 681-694).

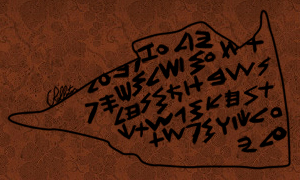

The format for each entry follows a standard pattern. Namely, there is reference to the number of the inscription within this volume (i.e., numbers 1-704), then there is descriptive title for the inscription (e.g., “#357, Epitaph of Shappira with Aramaic wall inscription”), followed by a reference to the approximate date of the inscription (e.g., “1 c. CE” = 1st Century CE). A basic description of the inscription is then given (e.g., “An inscription of four letters, cut in the soft rock, and blackened in, above the loculus of one of the lower burial rooms”). Normally, there is reference to the find spot, the present location, the department of antiquity number or museum number, and the measurements (e.g., for ossuaries). The editors made a concerted effort to personally inspect all available inscriptions (sometimes requiring travel to France, Germany, etc.). Also, there is reference to the precise date that the inscription was “autopsied,” that is, inspected, collated, measured, photographed. This is followed by the inclusion of the reading, provided in block script Aramaic, that is, the Jewish Script, for the Hebrew and Aramaic inscriptions, and the Greek and Latin script for inscriptions in those languages. In addition, different readings are also often provided under the rubric of “App. Crit,” that is, as a “critical apparatus,” along with reference to the scholar that proposed the reading. There is also a transliteration and a translation of the inscription. For the majority of inscriptions in this volume, black and white photos are also provided, although for a few of the inscriptions it was not possible to provide a photo. In such cases, hand copies are normally provided. Then there is a “Commentary” on the inscription, replete with things such as a discussion of orthography, phonology, prosopography (when appropriate), inscriptions with similar contents, meanings of names (when this can be determined).

Readers of this volume will find very fine, thorough entries for the inscriptions. Sometimes the inscriptions in this volume are, of course, partiucarly well known. For example, included in this volume are the “Uzziah Plaque” reading: “Here I brought the bones of Uzziah King of Judah; and not to open” (# 602) and the Greek warning sign from the Temple Mount: “No foreigner is to enter within the balustrade and forecourt around the sacred precinct. Whoever is caught will himself be responsible for his consequent death” (#2). There are particularly judicious discussions of inscriptions such as the “Ya’akov (‘James’) Ossuary” (i.e., #531, without provenance), and the Talpiyot Tomb known as the “Yeshua’ Family Tomb” (#473-478). Moreover, there is also a very useful synopsis of the salient points regarding the Sarcophagus of “Queen Sadan,” a burial inscription known for more than a century, but still the subject of substantive discussion (#123). Naturally, some will find the references to professions to be of interest. Although these are not very common, there are a few, such as the ossuary of “Yehosef son of Hananiah, the scribe” (#86). References to aspects of religion are also present at times. For example, there is reference to “Hananiya the son of Yehonatan the Nazirite” (#70), and several references to Proselytes to Judaism, including a certain” Ioudan the Proselyte of Tyre” (#174), and a certain “Ioudas son of Laganion the Proselyte” (#551). Of much interest also are the ossuary of “Megiste the priestess” (#297) and references on ossuaries to “Korban” (#466), a term also known from the Greek New Testament (among other ancient literatures). Of course, the famous ossuary inscription stating that “No one has abolished his entering [into death], not even El’azar and Shapira” (#93), receives a through treatment, replete with discussion of the different readings of Frank Cross and Joseph Naveh. There is also reference to a certain “Menahem” from the priestly course of “Yakim” (#183), and an ossuary of a certain “Yehohana” who was the granddaughter of the Caiaphate “High Priest Theophilos” (#534). Sometimes very useful linguistic data can be mined from the ossuary inscriptions, such as the fact that Semitic tsade can be represented in Greek with the psi, as the Semitic and Greek forms of the same name are given (see #309). Naturally, there are a few references to the prohibition of removing the bones (#507, 385). In sum, this volume is a treasure trove of data for scholars working in a wide variety of fields.

This really is a priceless volume. Those that purchase it will always be grateful they did. Those that do not purchase it now will regret that decision. Ultimately, these volumes will be the gold standard for the next generation, perhaps longer. I recommend this volume completely and without reservation. Those wishing to order this directly from the publisher can do so here: http://www.degruyter.de/cont/fb/at/atMbwEn.cfm?rc=42316 or Tel: 857-284-7073.

Christopher Rollston, Ph.D.

After this review was posted on this blog, several people contacted me to note that the term “Arab Conquest” is problematic. This term does occur within this volume (e.g., pages v and vii). Within this volume the term “Muslim Conquest” also occurs (e.g., page 26). It seems to me that the latter is preferable and more accurate historically, although the term “Rise of Islam” might be even better. In any case, I will be in touch with my contact person at de Gruyter to suggest that the terminology be modified (i.e., in subsequent volumes within this set). My thanks to those that contacted me with this notation.